PAST ISSUES

ISSUE No.1 WATER

In our premier issue we start with the source of all life: water. The Water Issue travels to the ends of the earth and beyond - from Central Africa, to Sweden, to the Palestinian Territories, and even into Outer Space. A movie producer takes a break from the high stress world of Hollywood to learn to surf - a 1 week vacation turns into 1 year as she becomes a student of water the "greatest teacher I have ever known" - Philippe and Alexandra Cousteau share the Legacy of their grandfather's love for the ocean - the obsession with bottled water falls under scrutiny...and more.

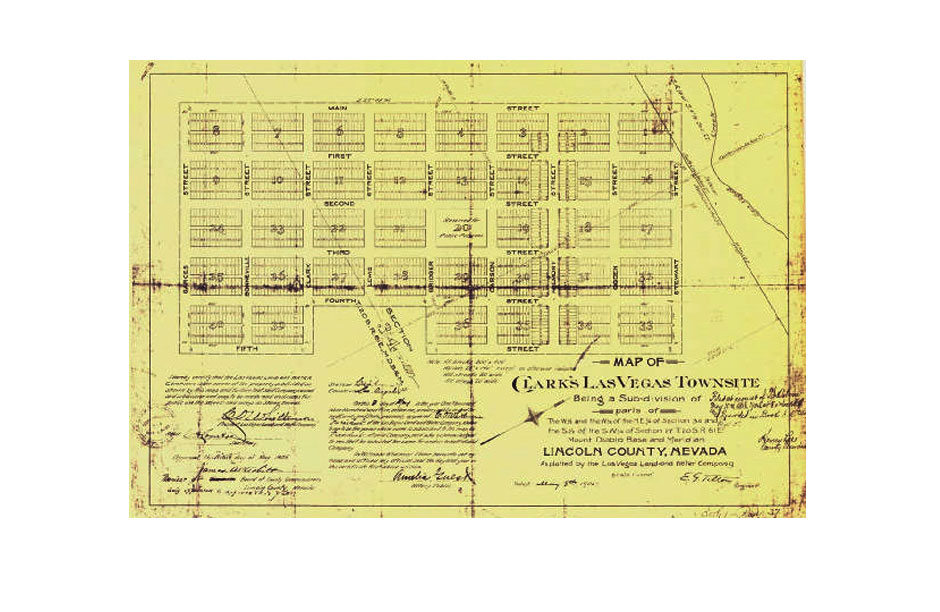

The first map of Las Vegas when it was a small settlement in the desert

The first map of Las Vegas when it was a small settlement in the desert

Aerial view of the infamous water fountains of the Hotel Bellagio

Aerial view of the infamous water fountains of the Hotel Bellagio

Water Wars : Las Vegas

By Matt KelemanLas Vegas shouldn’t exist.

This was my opinion before I migrated from wet, sinkhole-ridden Florida to the inhospitably arid Las Vegas Valley. It’s also an opinion shared by many of the ranchers that live hundreds of miles north on both sides of the border between Nevada and Utah, who fear their way of life threatened by Las Vegas’s unquenchable thirst for water.

Seven years later, I no longer feel that Las Vegas shouldn’t exist, not because of an adopted hometown bias. The area has always served a purpose. The 600-square-mile valley itself has been populated by indigenous people for thousands of years, drawn to the spring waters that inspired Spanish explorers to christen the land “The Meadows,” or Las Vegas. By the late 19th century a handful of settlers used the land for agriculture. In 1905, a railroad was built, 600 plots of land were sold, and a city began to take shape. Legalized gambling, the building of the Hoover Dam, mining, lax divorce laws and World War II defense factories all set the stage for the casino-resort booms of the ’50s and ’90s. Growth became the industry on which Las Vegas’s economy depended on.

In 1922 the Colorado River Compact divvied up the waters from the Colorado River between 7 Southwestern states, allocating the least amount (4 percent) to Nevada. No one ever dreamed Las Vegas would exist, and provide a miraculous watering hole for its 1.9 million residents and upwards of 18 million visitors a year. Until the ‘70s Las Vegas relied exclusively on its own groundwater. Five decades after the Colorado River Compact, Clark County began tapping Nevada’s 2 percent allotment, or approximately 300,000 acre feet per year. Most growth since the ’70s was largely fueled by that 4 percent. The Colorado River, however, is fed by melted snowpack, which in turn is fed by precipitation that has been severely affected by climate change. Each year from 2000-2005, Lake Mead averaged half of the inflow it received in 1999.

The waterline has continued to drop despite substantially higher inflow levels in the last few years. Clark County now obtains 90 percent of its water from its Colorado River allotment, and is installing a third intake valve several hundred feet below Lake Mead’s giant bathtub rings that indicate how much the level has fallen. The Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) is now looking north, intending to build a pipeline to tap into 170,000 acre-feet per year of groundwater from five hydrographic basins in eastern Nevada.

The battle over that pipeline is the potential Sarajevo of the coming water wars. SNWA General Manager Pat Mulroy says there will be little to no negative impact on the environment, and that engineering will allow snowpack runoff to quickly and efficiently refill underground aquifers. The farmers and ranch owners of northern Lincoln and White Pine Counties, supported by the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada (PLAN), passionately oppose the construction of the pipeline. Dr. James Deacon, a retired professor of environmental studies at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, co-authored a report for the September 2007 issue of BioScience magazine that predicts the aftermath: “Consequent declines in the water table, spring discharge, wetland area and streamflow will adversely affect 20 federally listed species, 137 other water-dependent endemic species, and thousands of rural domestic and agricultural water users in the region.” Greasewood, which prevents wind erosion, could disappear, and the region could experience dust storm conditions similar to those that afflicted Owens Valley after its water was diverted to Los Angeles in the early 20th Century.

Mulroy is fighting to have the pipeline built by 2019. PLAN’s Launce Rake says that the water obtained by the pipeline is a temporary fix for a permanent problem, will cause an irreversible ecological disaster, and suggests the SNWA would better serve Las Vegas if it put all of its efforts into conservation efforts above and beyond its popular turf reduction program, which paid residents to “desertscape” their yards. The organization plans to file a series of petitions to prevent the pipeline from being built, which Mulroy confidently predicts will be unsuccessful.

This is what present day water wars look like — local water authorities and their steely reps battle it out with concerned citizens and ever-present environmentalists. Another contemporary scenario places the people against a corporation such as French based Suez-ONDEO or RWE-Thames Water of Germany, which present themselves to local water authorities as a financial answer to the woes that come with the responsibility of management and upkeep of municipal water supply. Indianapolis, Milwaukee and Gary, Indiana are among more than 500 cities and regions in the US that are currently paying private corporations for their water. Atlanta — which was three months away from running completely out of water in 2008 — and Croton, California successfully fought against a foreign corporation that attempted to usurp their public rights to “the commons.”

In their book Blue Gold, which outlines the global water crisis and the debate, surrounding it, Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke slap the reader with staggering statistics. Here’s one chilling look into a future only 15 years away: “By 2025, the world will contain 2.6 billion more people than it holds today, but as many as two-thirds of those people will be living with absolute water scarcity. Demand for water will exceed availability by 56 percent.” A grizzly result of such an equation will switch out “oil” for the word “water” in today’s globally fought wars over the limited resource.

If the SNWA wins their pipeline and the protesters are right, areas of Lincoln and White Pine Counties will be decimated. If petitions prevent the pipeline from being built, climate change continues to affect snowpack and extreme conservation is not put into practice, Las Vegas very well may not exist in the future. Even a temporary interruption of water could wreck the economy and turn the Vegas Valley into a 600-square mile fire hazard. Most of its two million residents will have to be relocated. By that time there will be fewer places to go as more cities take on the same issue.

What’s happening in Vegas is a sign of things to come across the country and worldwide. United States citizens need to adopt a universal conservation conscience now to minimize the effects of future water struggles, and not be content to point the finger at the reclaimed water-fed fountains at the Bellagio Hotel as a symbol of waste ( or as a symbol of water conservation for that matter) without knowing how long water will flow freely in their own kitchen sinks.