PAST ISSUES

Bashir makes his way through a wheat field on his way down to the village of Gangar (within Govind Pashu Vihar Wildlife Sanctuary) in the hopes of receiving payment for milk that he had sold villagers a week or so before. Photo by Ben Lenzner.

Bashir makes his way through a wheat field on his way down to the village of Gangar (within Govind Pashu Vihar Wildlife Sanctuary) in the hopes of receiving payment for milk that he had sold villagers a week or so before. Photo by Ben Lenzner. Shirafat Ali finds a moment to rest and yawn with one of his buffalo. Photo by Ben Lenzner.

Shirafat Ali finds a moment to rest and yawn with one of his buffalo. Photo by Ben Lenzner. photo by Ben Lenzner

photo by Ben Lenzner photo by Ben Lenzner.

photo by Ben Lenzner. Ali Sen sits outside the shell of his previous dehra (home) in Govind Pashu Vihar Wildlife Sanctuary. photo by Ben Lenzner

Ali Sen sits outside the shell of his previous dehra (home) in Govind Pashu Vihar Wildlife Sanctuary. photo by Ben Lenzner

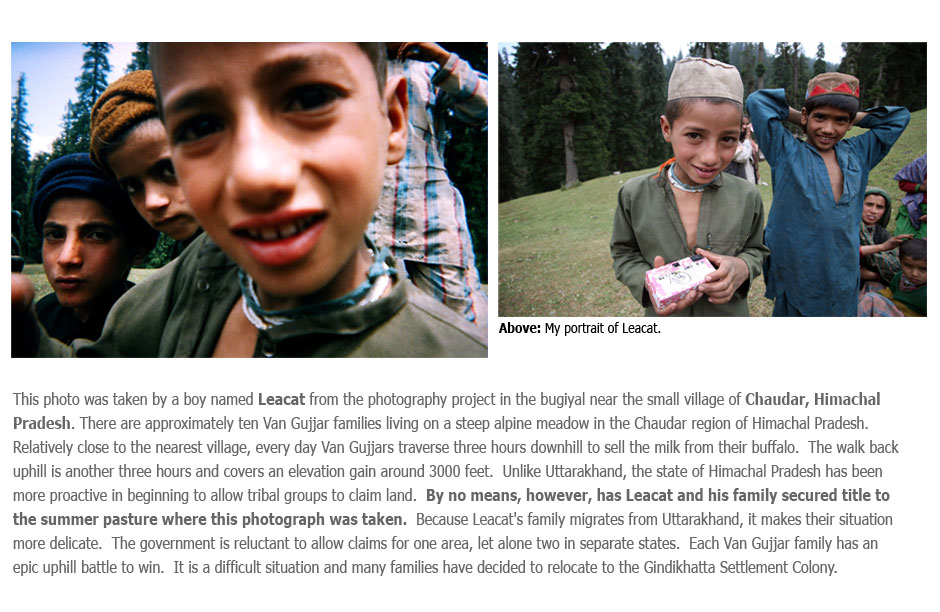

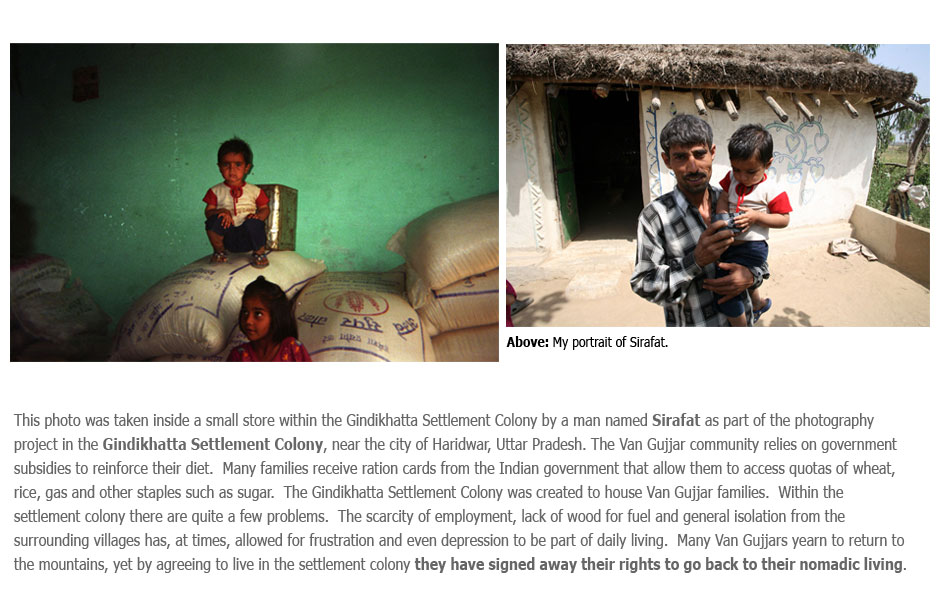

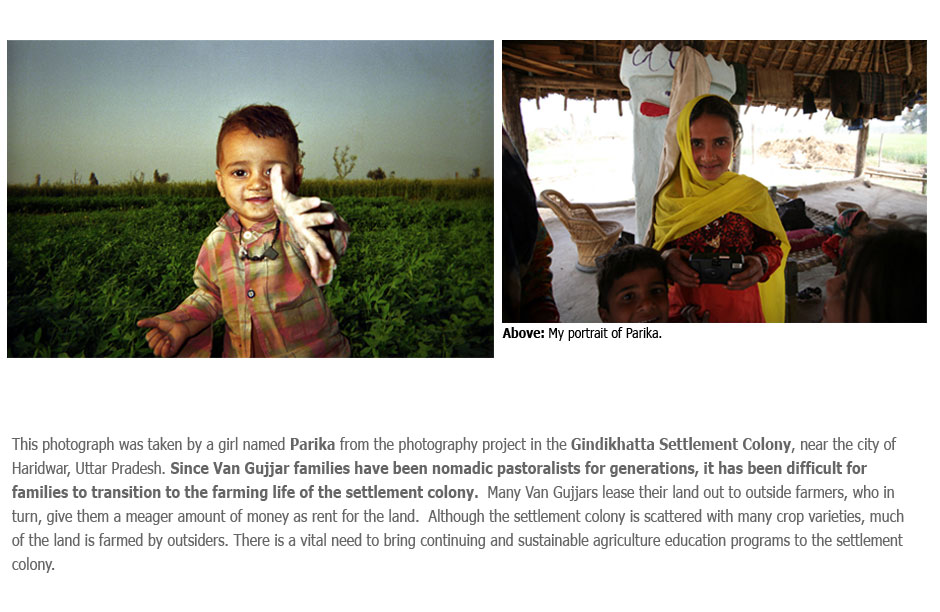

In Chaudar, photographs are returned after a trip to the nearest photography studio in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh.

In Chaudar, photographs are returned after a trip to the nearest photography studio in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh.

Migrating Through Northern India in Search of Indigenous Rights

By Ben LenznerFrom New Delhi to Dehradun, the capital of the Indian state of Uttarakhand, the train journey lasts six hours, climbs the lesser Himalayan Range once, crosses state lines twice and finally comes to a rest in the fertile Doon Valley at the foothills of the Himalayas. Dehradun is the last stop and the end of the railway line. To the east, Uttarakhand is bordered by Nepal. To the north, it shares a frontier with Tibet. To the west, rests the mountainous Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, largely known for the town of Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama resides. Huge mountains are everywhere. It is possible to take a car part of the way to other regions of Uttarakhand, but at some point you’ll have to get out and walk. And if you do walk, or even drive these Uttarakhand Himalayas, you’re bound to see, beside mountain roads, the Van Gujjar community and their vast herds of buffalo.

In 2005, I arrived in Dehradun on the early morning train from New Delhi in order to work. I had received a fellowship from the American India Foundation and my task was to help a local NGO, Rural Litigation and Entitlement Kendra (RLEK), integrate modern beekeeping methods with traditional beekeeping techniques in the hope that we could organize sustainable wildflower honey production throughout multiple villages of the Garhwal region of the Uttarakhand Himalayas. Due to a delay in funding, that project never got off the ground. Yet during the ten months I lived in Dehradun, I started to work with a separate NGO, the Society for Promotion of Himalayan Indigenous Activities (SOPHIA). Through this organization and with the help of its determined director, “Manto” Praveen Kaushal, I was introduced to the Van Gujjar community. In June of 2006, my fellowship ended and I headed home. Yet for two years, I kept thinking about the Van Gujjar community and their struggles. In March 2008, I made a decision to return to Dehradun. Yet this time, I decided to return with 100 disposable cameras. Journalists, I reckoned, had taken enough photographs of these people by side of the road. It was time to get cameras to Van Gujjars in the forest, so that they could capture and share their reality.

Van Gujjars are a nomadic indigenous community that has lived, migrated and practiced Islam throughout these mountains for generations. For Van Gujjars, the buffalo is sacred. This animal is their lifeline and Van Gujjars support themselves, more or less solely, through the selling and bartering of buffalo milk. In India, the price of milk depends on the fat content. The richer the milk, the more expensive it is for the consumer. The Van Gujjars and their buffalo are forest dwellers. In their constant meanderings, the buffaloes eat shrubs, leaves and grass. This means healthy buffaloes, which allows for milk with a higher fat content. Van Gujjar families milk their buffalo early in the morning in order to transport fresh milk so that it can reach the local market on time. The milk is used for chai and ghee, while some wealthier families will, from time to time, make yogurt. The rest of the day’s milk gets transported from the forest to a local village to be sold at market or through the milk cooperative that has been set up by the Society for Promotion of Himalayan Indigenous Activities (SOPHIA), a local Dehradun-based non-governmental organization (NGO). Depending on the resources of each family, Van Gujjars may own anywhere from five to fifty or more buffalo. And anyone will tell you that the milk from these buffalo is sweet and delicious. Although milk is plentiful and it is common for a Van Gujjar family to offer a bowl of sweet milk to guests, life in the forest is hard and the daily struggle to survive is constant.

In the winter, Van Gujjar families live in the plains of Uttarakhand and the adjoining state of Uttar Pradesh. As the winter becomes a short Indian spring and then summer quickly follows, the plains dry up, and there is neither food nor water for the buffaloes. Towards the beginning of May, Van Gujjar families pack up their homes and begin to migrate to their Himalayan bugiyal (alpine meadow). These bugiyals are below snowline and each family tends to return to the same alpine meadow each year. The migration occurs at night. Entire extended families and their buffalo walk in darkness in order to take advantage of both the regional road systems scant of traffic and the cool of the evening air. The exodus from the plains to the bugiyals can take up to three weeks and each family covers a tremendous amount of elevation and distance. This mass familial migration is not easy and the journey is only over when the family has reached its summer bugiyal. These high altitude alpine meadows offer unlimited grazing for the buffalo and the fresh water of mountain streams is plentiful. A few months later, at the end of summer, when the mountains start to get cold and the night air bites crisp, each family packs up their summer home and returns to the plains for the winter.

This migratory life has become complicated in the last three years. In the winter, many Van Gujjars reside in Rajaji National Park, while in the summer a small group of families live within the boundaries of Govind Pashu Vihar Wildlife Sanctuary. Although these wilderness areas are well intentioned, the creation of the two has had dramatic effects on the Van Gujjar community. The Forest Department of Uttarakhand (which controls these two national parks) claims that Van Gujjars and their buffalo are destroying the forest. Manto Kaushal, the director of SOPHIA, points to the fact that Van Gujjars have lived in these areas for countless generations and that it is logging and the constant exploitation of natural resources by private companies that depletes these forest regions. In January 2008, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act was passed in the Indian Parliament. The first comprehensive indigenous land rights act ever approved in India, this bill gives indigenous groups the power to finally obtain rights to their traditional homelands. Although there is much red tape to be conquered before land rights become a reality, at this moment in history, Van Gujjars have the legal power to claim the forestland they have lived on for generations.

For the past two years I have been collaborating with SOPHIA, the lone NGO working to secure land rights for the scattered Van Gujjar community. It was in 2008, that we began a multi-faceted documentary photography project that distributed more than 100 cameras to Van Gujjar women, children and men. Over the past two years, relocated Van Gujjars in the Gindikhatta Settlement Colony and Van Gujjars who migrate twice a year from the plains to the mountains have photographed aspects of their lives that are meaningful and important to them. These photographs and the stories that are attached to each image are essential in that they allow us to begin to archive vital knowledge from a community that is on the forefront of tribal rights in India. The future of the Van Gujjar community is uncertain. Their pictures are some of the only records and visible traces of the Van Gujjar footprint. At some point, these visual documents may become an integral element in their legal claim for tribal land rights.

Traveling back by train from Dehradun to New Delhi, the only instance where signs of human life are scarce is during the short stretch through the Shivalik Mountains, an area where the community resides in the winter. It is estimated that by 2025, India will be the most populous nation on the planet. Each summer, it gets more confusing for the Van Gujjar community as to why they are slowly being denied access to land they have lived on for generations. The community knows very little about the Forest Rights Act and many Van Gujjars are illiterate. Pursuing legal title to this land will be a monumental struggle. Moreover, the community needs to claim rights for different areas in two separate states. This is an unprecedented task. As large cities in India expand and more of the Indian population begins to reap the benefits of the global economy, it is indigenous communities like the Van Gujjars whose culture, traditions and history may be lost before the first rupee ever trickles down. As globalization brings wealth to unknown pockets of the earth, cultures and traditions shift and disappear as rapidly as the Himalayan glaciers around them.