PAST ISSUES

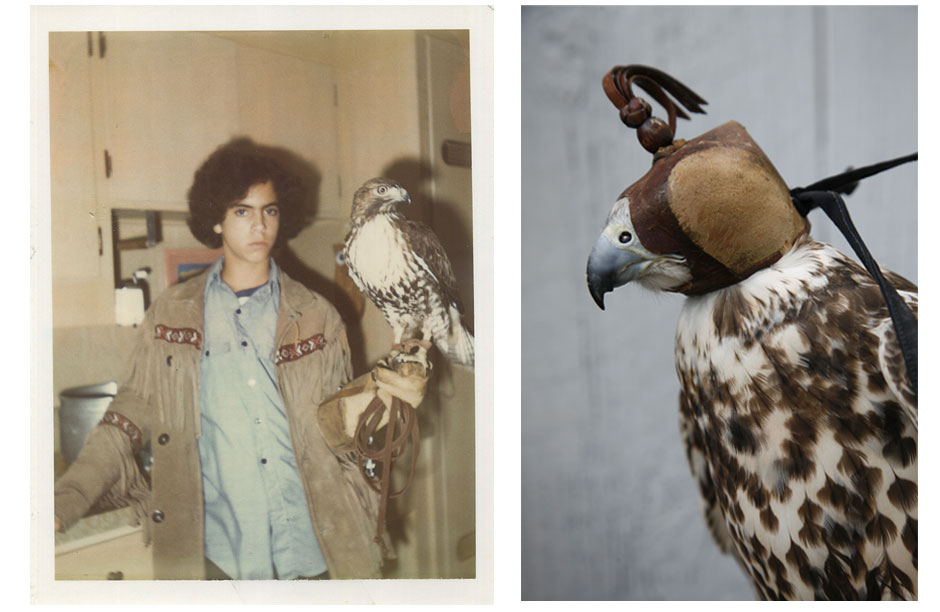

Image Left: young Jeff Diaz with Vicki, his first Red-tailed hawk. Image Right: Willow, a female Saker falcon from the Ronin Air squadron. Image by Claire Scoville.

Image Left: young Jeff Diaz with Vicki, his first Red-tailed hawk. Image Right: Willow, a female Saker falcon from the Ronin Air squadron. Image by Claire Scoville. Image by Claire Scoville

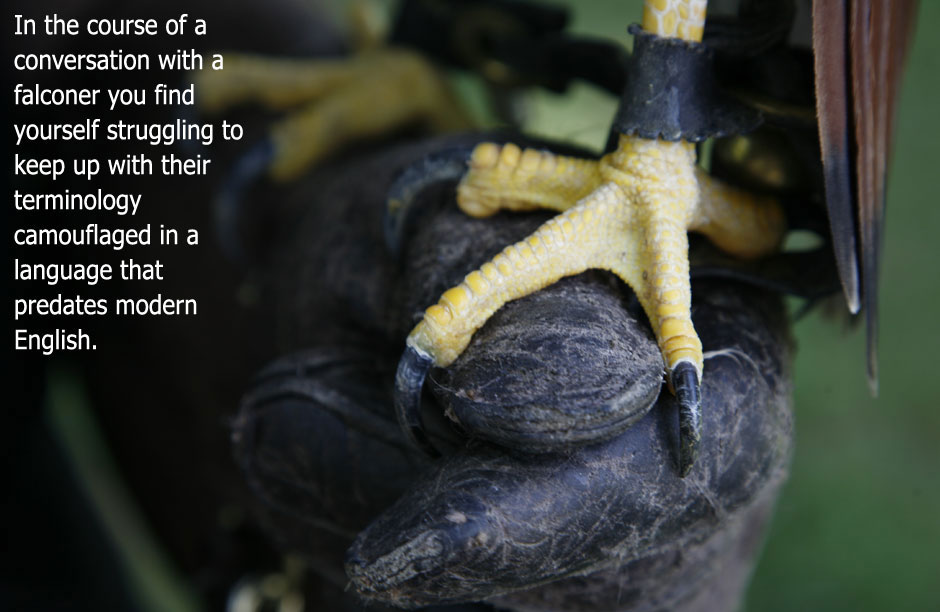

Image by Claire Scoville Portrait of Chopin, a male Saker falcon from the Ronin Air squadron. Image by Claire Scoville.

Portrait of Chopin, a male Saker falcon from the Ronin Air squadron. Image by Claire Scoville.

A Falconer’s Tale

By Nicole Davis“Her name was Vicki” short for Victoria Xaviera. “She was named after a girl I had a crush on and the ‘Happy Hooker’ Xavier Hollander.” The woman in question is a Red-tailed hawk and it was the first bird professional falconer Jeff Diaz caught and kept long enough to give a name. He was 12 years old and living in the hippie-haven of the San Francisco Peninsula in the 1970s. His passion for falconry was sparked two years before after reading T.H. White’s The Once and Future King about the childhood of King Arthur. “There’s a chapter where Merlin turns young Arthur into a Sparrowhawk and he’s able to speak to the falcons and hawks in their own language.”

In the course of a conversation with a falconer you find yourself struggling to keep up with their terminology camouflaged in a language that predates modern English. They use phrases like “jessed up”, “making in” and “chamber raised”, and they give each other nicknames that reflect the species of falcons they fly. Jeff’s nickname is Saker and he currently owns 7 Saker falcons, one of the larger species of falcons and the best for carrying out the work Ronin Air, Jeff’s commercial falconry company, has been hired to do for the past 11 years.

Falconry dates back 4,000 year ago, but the first time falconry was ever applied for commercial use in the United States was in 1996 to clear take off and landing pathways around the John F. Kennedy Airport. Today JFK and several airports across the country implement the use of falcons to protect both birds and human passengers as part of the B.A.S.H program (bird aircraft strike hazard). It is estimated that 75% of birdstrikes go unreported. Until US Airways flight 1549 made its infamous crash landing in the Hudson River due to a geese airstrike, most people didn’t even know it was a risk.

In April 2002 Ronin Air received a call from the County of Santa Barbara about a seagull problem at the Tajiguas landfill just a few miles from Arroyo Quemado beach. ” I stopped by one afternoon to survey the spot and I couldn’t believe how small the garbage patch was. I thought ‘piece of cake’, nicest cleanest landfill I’ve ever seen.” All they needed him to do was fly his birds of prey over the site for an extended period of weeks or months and scare the seagulls away from the landfill site permanently.

“What I didn’t know before I started was that at 5pm every day 10,000 Western and California gulls upon having their food covered up for the night after they closed the landfill would fly several hundred yards to the very nearest beach.” The water just off the beach was contaminated with .2000 (parts per million) of coliform bacteria borne from seagull feces. “They were testing the beach every Monday for the last several years and it failed miserably. It was red-tagged dangerous for surfing, swimming or diving most weeks of the year. Several environmental groups such as Heal the Bay, Heal the Ocean, and Sierra Club were aware of this and through negative publicity the public was aware as well. If only I knew!”

There were several challenges that the job posed. Some of the seagulls had been feeding from the same landfill for up to their entire lifespan (17-18 years). Plus, seagulls breed on the Channel Islands 20 miles off the Coast of Santa Barbara and return with a new brood determined to survive. Jeff and his fleet of falcons were expected to clear the area of several generations of seagulls.

“In just 21 days the bacteria count went from .2000 (fcu) to .0004 (fcu) or 2 thousand parts per million to four parts per million. They thought the DNA test was a mistake and retested. It was accurate!”

On Aug 1, 2002 Ronin Air and the historic success of the first landfill to be cleared of seagulls by a commercial falconer on the California coast was featured in the LA Times. Then the Associated Press ran the story nationally, and the jobs began rolling in for Ronin Air to abate seagulls form resorts, landfills, and local businesses.

Just a few years later as the commercial falconry business began to grow Jeff’s competitors moved in, and he found himself scrambling for jobs. All of a sudden, “Life sucked. I had to give up the beach pad. I lost my local trophy girlfriend. I was in debt, and really at the end of my rope.”

Just short of calling it quits, Jeff received another fateful call, but this time from an oil refinery on the east coast to rid them of Winter Starlings. A Starling is a beautiful bird with deep black plumage and white specks scattered across its body making each one look like a moving patch of night sky, but they are better known as the “rat of the sky” topping the common Rock Pigeon as the most reviled bird on the planet. The Starling is a native of Europe and since their introduction to the United States they have proliferated at unstoppable rates. Their migratory patterns glide them circuitously around the US and North America so that each state can develop their own unique and profound hatred for them. At the oil refinery it was simply a matter of health. Winter temperatures send Starlings on a hunt for warm places to roost. The oil refinery provides them just the warmth they need to get through the night, the morning, and possibly the whole winter. Finally hundreds have moved in and their feces is everywhere, which can transmit up to 40 different pathogens to humans. For the numbers people at the oil refinery this translates into potential worker’s comp and class action suits.

“They advanced us funds, and I drove across the U.S. with eight hawks, falcons and owls.”

The alternative to hiring Ronin Air, as many businesses continue to choose, is implementing an Avicide program. Several chemical avicides have been outlawed such as cyanide, strychnine, and arsenic, but there is one that is still legal in most states: Avitrol. Avitrol, also known as “Crazy Corn”, is a toxin that attacks the central nervous system neatly packaged to resemble a tiny grain. The pest birds are meant to ingest it and frighten the rest of the flock from the site by emitting a series of distress calls as their body goes into seizures. If enough is ingested the bird will die. Avitrol has made its way into the food chain when birds of prey, like hawks, owls and falcons, feed on the carcasses of poisoned birds causing their eggs to be too thin to carry to term. In 1975 Peregrine falcons were completely wiped out from the East Coast. This prompted a major Peregrine breeding and re-population effort by The Peregrine Fund led by Tom Cade a professor of ornithology at Cornell University.

“We are inspired and committed to providing environmentally-minded clients with an effective alternative to applying poisons,“ pledges Jeff. Most companies aren’t aware of falconry as an alternative, nor are they aware of how successful the results actually are. “After just 2 consecutive years the starlings never came back. We had safely, permanently relocated them without hurting or killing hardly any of them, and this is what we do all over the U.S.”

Now Ronin Air has a fleet of 12 birds and 3 master falconers managing the Ronin Air contracts. In Manheim, Pennsylvania master falconer Ash Cary is taking care of 7 Ronin Air birds as they rest up over the summer while business is slow. Ash is a former Navy Seal who was introduced to falconry 27 years ago by his godmother in Surrey, England where she ran the National Bird of Prey Center and School. He spent every summer there as a child, and the rest of the year shuffling between foster homes. His job is to fly the birds once a day to keep them conditioned and to continue training the younger birds. “When you’re trying to teach someone something, you always want to set them up to succeed, not fail.” This is the technique behind his training based in trust and positive reinforcement. “I haven’t lost a bird in 27 years.”

For Jeff Diaz the birds are far more than a business, “I have no human children. I treat my squadron birds as if they are my own.” While many of us are unaware of the impact these birds are having on our daily lives, from cleaning our beaches, guarding the health of employees, keeping toxins out of the environment and ensuring we as humans have safe passage through the air that is their true domain, the falconer and his squadron are fighting an invisible war around the clock.