PAST ISSUES

ISSUE No.1 WATER

In our premier issue we start with the source of all life: water. The Water Issue travels to the ends of the earth and beyond - from Central Africa, to Sweden, to the Palestinian Territories, and even into Outer Space. A movie producer takes a break from the high stress world of Hollywood to learn to surf - a 1 week vacation turns into 1 year as she becomes a student of water the "greatest teacher I have ever known" - Philippe and Alexandra Cousteau share the Legacy of their grandfather's love for the ocean - the obsession with bottled water falls under scrutiny...and more.

Madonna shows her appreciation for bottled water in an infamous scene from her documentary "Truth or Dare" (1991)

Madonna shows her appreciation for bottled water in an infamous scene from her documentary "Truth or Dare" (1991)

“Bottlemania” Explained

By Nicole DavisWhy should we stop drinking bottled water?

Here’s a catalogue of reasons that would put Homer to shame:

88% of empty plastic water bottles in the United States are not recycled – that translates into 30-40 billion plastic water bottles a year – that’s right, billion; It takes an estimated 450-1,000 years for plastic to biodegrade in a landfill; Captain Charles Moore of the Algalita Marine Research Foundation discovered a mass of trash composed primarily of partially biodegraded plastic pellets twice the size of Texas in the Pacific Ocean. Now known as the “Pacific Trash Vortex” or “Gyre”, the partially biodegraded plastic pellets have been found in the dissected stomachs of both fish and seabirds; Americans spend about $16 billion a year on bottled water; If the water we use at home were to cost what the cheapest bottle of water costs, our monthly water bills would run $9,000; Peter Gleik of the Pacific Institute estimates that the total energy required for every bottle’s production, transport, and disposal is equivalent, on average, to filling that bottle a quarter of the way with oil*; It can take nearly 7 times the amount of water in the bottle to actually make the bottle itself; Neither the EPA nor the Food and Drug Administration test or account for the water quality of bottled water; Cleveland officials tested Fiji spring water and revealed 6.3 micrograms of Arsenic per liter; Phthalates, a chemical in plastic proven to leach into bottled water, inhibits the male hormone testosterone, can lead to hormonal imbalance in both men and women, and can also effect child development; Bisphenol-A (BPA), a chemical found in plastic and proven to leach into bottled water, mimics the female hormone estrogen, can heighten the risk of breast cancer in women, can lead to hormonal imbalance in both men and women, and can effect child development; Each day in Fiji, more than a million bottles of their local spring water are prepared for shipment off the island, while more than half the people in Fiji do not have safe, reliable drinking water…and the list goes on.

Despite all of this, I am going to be honest right now: I still drink bottled water. I have tried to figure out why, against all my better judgement, I continue to keep up such a shameful habit. As I examined my habit it began to look more like an addiction. The environmental writer Elizabeth Royte most aptly categorizes the phenomenon as a form of mania, “bottlemania”, she calls it – describing it as, “One of the greatest Marketing Coups of the 20th and 21st Centuries.”

In her book Bottlemania, Royte chronicles her in-depth investigation of the bottled water industry and the consumer psychology behind its success. The bottled water industry spends upwards of $160 million a year on bottled water ads in the United States. That’s paltry in comparison to the $16 billion Americans spend yearly purchasing the stuff. “Sales of bottled water have already surpassed sales of beer and milk in the United States and by 2011 are, by some analysts, expected to surpass soda, of which Americans drink more than fifty gallons per person a year.”(Royte 7). Bottled water has become so integral that it has reshaped our urban landscapes – “…our cars, stair masters, and movie theater seats have been redesigned to accommodate them…” (Royte 17) – while water fountains, like street-side phone booths, are becoming a quaint relic of the past.

So how did this all happen? When I dug deeper I realized that my drinking habit was derived from a very visceral sense of fear – fear of the tap. Bottled water companies have been working on getting me to this place of fear for a long time, but before it was fear, it was vanity they targeted.

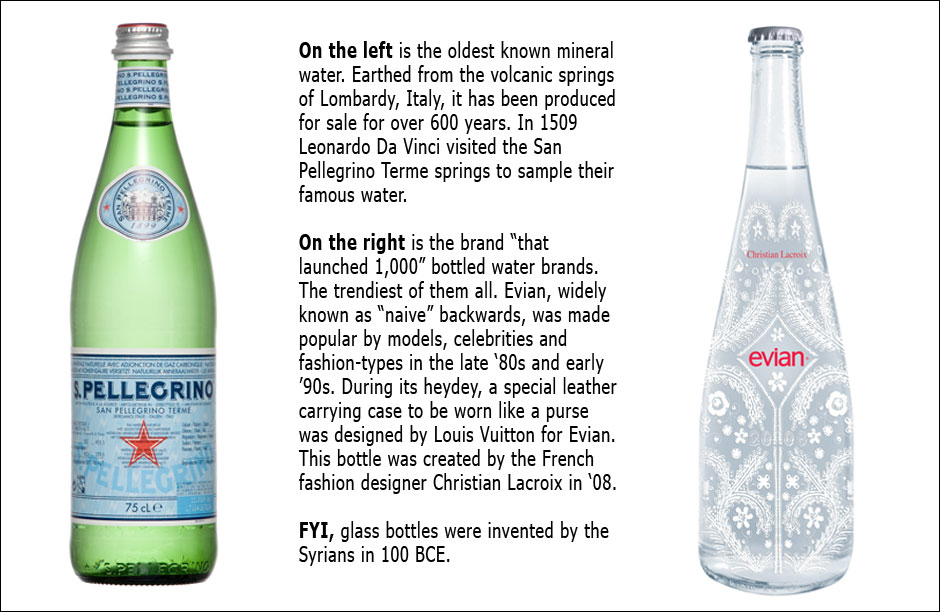

At one time mineral water and natural spring water were only for the wealthy, famous, the glamorous, and the beautiful. For the consumer that does not fall under any of these monikers, bottled water was there to give them a sense, “…that a touch of luxury was not beyond their means.”(32). In 2002, the bottled water industry supported a campaign called “Pour on the Tips”, providing tutorial DVDs and pamphlets to teach waiters how to pocket more tip money by embarrassing their clients into buying bottled water – and somewhere along the way “8 glasses a day”, which has never been scientifically proven, was established as gospel. But, when the industry saw the opportunity to capitalize on a larger consumer pool than just those trying to keep up appearances, they began working on new marketing angles.

As bottled water began its descent into “democratization”, the bottled water industry needed to ensure its competitor wouldn’t bar the way. The competitor of bottled water is like no other competitor in the capitalist world – it’s 100% cheaper, tested and proven to be safe to drink, and available at the turn of a handle. The bottled water industry needed to figure out a way to take down the tap.

This is where fear came into play. Although this approach began as early as the 90s, around the turn of the new millennium, bottled water companies began keying into the energy of Y2K paranoia, of post-9/11 preparedness, and of global warming’s gift of extreme weather catastrophes. Consumers began exhibiting themselves as people stocking up for a nuclear fallout. We began buying into fears of terrorist attacks on municipal water supply, fears of being stranded without water, and as a result, fear of the tap. All of a sudden the water we had always trusted seemed dubious. Bottled water became a dependable commodity floating in to the rescue from an untouched source.

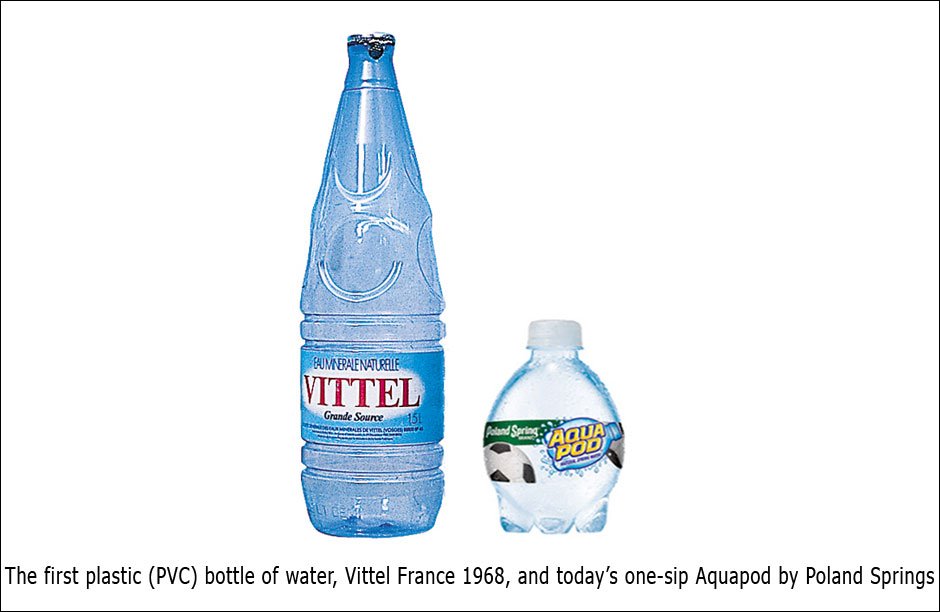

The final step for the bottled water industry was to make bottled water so omnipresent, so convenient, and such a basic part of our daily lives that we now can barely recall a time without it. “Like ipods and cell phones, bottled water is private, portable, and individual.” (42). There’s a brand for everyone: Ethos – for the ethically minded, Vitamin Water – for those who want their water to do more for their bodies, Smart Water – for those that think they know better, and then there’s the Poland Spring’s “Aquapod”, for those just looking for a sip of refreshment. The largest beverage companies in the world, Coke and Pepsi, inevitably needed to get in on the act. With Dasani and Aquafina, respectively, the beverage juggernauts cleverly put the tap to work (their bottled water is filtered and treated tap water).

LIKE WATER FOR CHOCOLATE: THE STORY OF NESTLE WATERS

“I feel privileged to be drinking straight from the ground, a rare possibility in this age of ubiquitous animal-borne diseases and pollution. I can choose from nearly a thousand types of bottled water on store shelves, but I can’t, with infinitesimally few exceptions, drink form a naturally occurring body of water. Magically appearing from inside the earth, spring water has always had a powerful mystique. Civilizations have fought over such sources. But I’m not feeling any mystique right now. What I am mostly thinking as I sip…is the driving force behind a multimillion-dollar plant that directs three hundred million gallons of water a year into the farthest reaches of New England, New York, and parts (out) west.” (Bottlemania p.3)

The excerpt above is also from Bottlemania. It is Elizabeth Royte’s description of her experience in the woods of Maine, when an employee of Poland Springs (part of Nestle Waters North America) took her to drink directly from one of their spring water sources bubbling up from the ground, pure and filtered through centuries of glacial sediment.

Nestle, the swiss-owned company responsible for hot cocoa among dozens of other food and beverage products including Similac baby formula, Purina pet food, Haagen Daz ice cream, and the infamous Baby Ruth candy bar, is the largest bottled water corporation in the world.

Nestle Waters North America generates 15 different brand labels of bottled water. Behind each of these names is a source of fresh water – usually a spring – that was once managed locally, but Nestle strikes a hard bargain. Small water wars crop up around these sites where locals rally to protect their natural resource. In Maine, the source of Poland Springs, one local (Fryeburg) resident was quoted by Royte:

“This Swiss corporation came into our tiny rural American community and bullied residents and bribed officials to look the other way while they had their way with our water supply.” (184).

Nestle Waters North America makes over $8 billion in profits a year. The contention in Maine is an ongoing battle. While across the United States citizens in Michigan, Florida and elsewhere mimic the battle against Nestle in Maine.

The horizon of “bottlemania” recovery is far off in the distance, but the journey has already started. Bottled water sales are slightly down from record highs in 2007. The nonprofit organization, Food &Water Watch, has initiated a successful “Take Back The Tap Campaign”, and cities around the world are just starting to ban bottled water. This past July in Australia, the town of Bundanoon became the first town in the world to put a total ban on the sale of bottled water. Last year, Toronto initiated a partial ban on bottled water, forbidding its sale in city-run facilities. While Governor Paterson of New York, announced this past Earth Day that he will be issuing a ban on bottled water in all New York state agencies.

It appears as though bottled water is slowly falling out of fashion – “Fashion drove a certain segment of society to embrace bottled water in the first place, and fashion (green chic, that is) may drive that same segment to reject it.” (169).

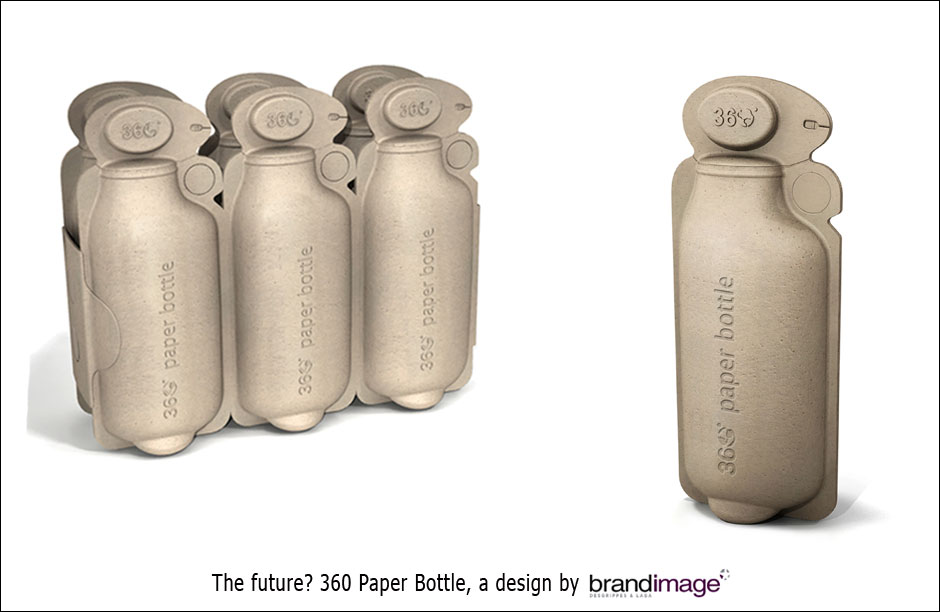

Royte offers up a few solutions. Being highly aware of the strain the bottled water industry puts on landfills, (Royte wrote an entire book on the cycle of waste, titled “Garbage Land”), her first advice is to step away from the single-serve plastic bottle of water and move towards a portable, multi-serve refillable version. For tap concerns she points towards the option of filtration. Royte recognizes taps flaws and our rightful fear of the tap, but above all, Royte leads by example. She took the initiative to examine the facts about water today and to investigate the water she drinks. If we take on the same initiative and stop looking to bottled water to bail us out, we can rightfully ask our government to provide more funds and more focus on raising the quality of our drinking water.

*Bibliography: Bottlemania:Big Business, Local Springs, and the Battle Over America’s Drinking Water. Elizabeth Royte, Bloomsbury, 2009.