PAST ISSUES

Earth Day on the Gowanus Canal - Brooklyn, NY.

Earth Day on the Gowanus Canal - Brooklyn, NY. The author takes a canoe ride down the Gowanus Canal on Earth Day 2011

The author takes a canoe ride down the Gowanus Canal on Earth Day 2011 Trash still piles up along the old garbage thoroughfare of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, NY

Trash still piles up along the old garbage thoroughfare of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, NY The Gowanus Canal raises awareness about the trail our trash once took and where it end up now.

The Gowanus Canal raises awareness about the trail our trash once took and where it end up now.

On the Gowanus

By M.F. SandlerI remember going to a party on a roof in Alphabet City just a little after I moved to New York City ten years ago. On an early fall night, the party was filled with recent college graduates like myself. One woman gestured towards the rotting water towers and Brooklyn’s abandoned post-industrial waterfront, and cooed loudly: “Isn’t it beayooootiful?”

I remember thinking at the time: well, sure, but did you have to say it just like that? I was drawn to New York for its perverse, apocalyptic “beauty,” but I knew I was a cliché. I also knew that behind New York’s picturesque decay lay expensively remodeled “lofts” and money I’d never make.

Those water towers weren’t rotting because they were artistic, they rotted because New York had moved on, like it does. I don’t know what happened to my fellow reveler from my first days in New York. She’s probably found success, gotten married, had a child, and remodeled a brownstone, with a beautiful brand-new kitchen under a beautiful broke-down water tower.

I thought of her assessment again recently after a canoe trip along the Gowanus Canal, courtesy of the Gowanus Dredgers Club, a group dedicated to educating the public about the canal. Here I would see the rotten beauty of the city up close, without the safety of distance and elevation.

From the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth, the Gowanus Canal formed a crucial part of Brooklyn industry. At the end of World War I, it was “the nation’s busiest commercial canal.” Elizabeth Royte provides this happy statistic in her book Garbage Land: On the Secret Trail of Trash; she visited the Gowanus repeatedly during her quest to follow her household trash to its various and surprising ends. She writes that once trucks overtook barges as the main interior transportation, the Gowanus Canal became a dump: for sewage, for chemical waste from nearby factories, for the bodies of rats, pets, and people.

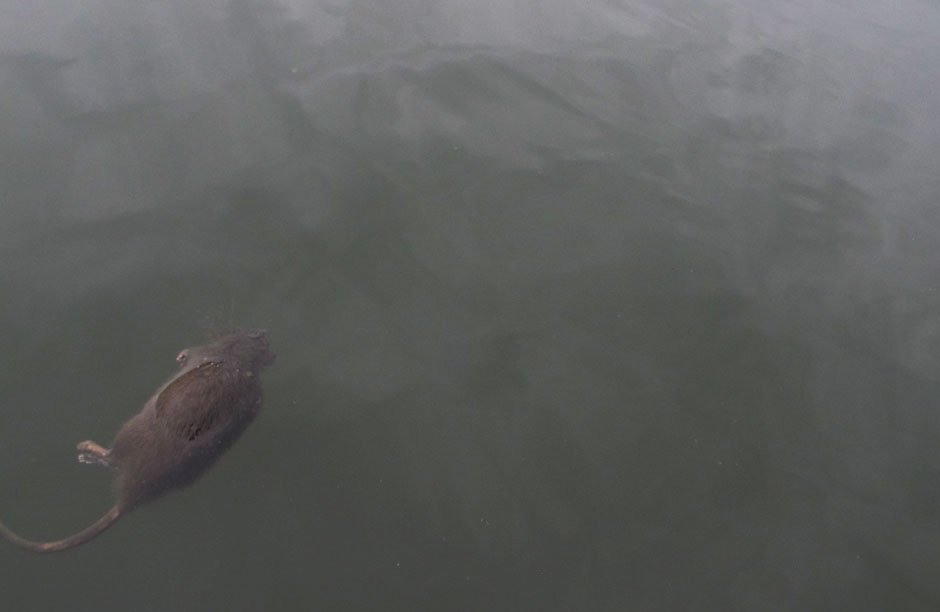

Partly in response to grass-roots efforts like that of the Gowanus Dredgers Club and reporting like Royte’s, the Environmental Protection Agency designated the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site in 2010. Meaning, the agency intends to seek redress from the companies responsible for releasing hazardous wastes into the canal. I booked my canoe trip on Earth Day – the same trip Royte took down the canal ten years earlier when her reporting began. As my small group paddled along the canal, we saw the water slicked over with the worst version of that familiar rainbow shimmer. In places, the water bubbled up as gasses escaped from whatever ungodly stuff was percolating below the surface. We began to count the dead rats. The water that dripped off of my oar turned my jeans brown in minutes.

Above the sea-wall, we could also see the sources of the devastation: what looked like a garbage processing facility, a cement factory, and huge vats. If the water towers were picturesque, the Gowanus was sublime: massive, terrible, and compelling. The nineteenth century Uruguayan-French poet Comte de Lautréamont once saw beauty in a “chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on a table” In the piled garbage, five stories high at least, it looked like a lot more than a sewing machine and an umbrella made some beauty there. 8 million stories of chance encounters seemed like a conservative guess: toilets and tires sprouted hangers and wires, bicycles battled air-conditioning units, and so on… I began to wonder about other meetings, happening below the surface and beyond my immediate comprehension.

Between these crime scenes, we saw signs of revitalization. We paddled by houseboats inhabited by adventurous bohemians, the backside of galleries, and a spanking new Best Buy store. Locals debate the compatibility of gentrification with efforts to repair the Canal’s substantial ecological problems. The plan to move the New Jersey Nets to downtown Brooklyn (accompanied by massive housing developments and shopping complexes, and fronted by Jay-Z and backed by Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov) is one of many expected to bring new money into the neighborhood, as well as more sewage overflow into the canal.

I wondered which ideas of beauty lay behind these fledgling projects. The people at the gallery openings must fantasize about the canal’s long-dead oyster beds… What would the loft-dwellers think while they stared out of their floor-to-ceiling windows onto a century of neglect? Did they feel some kind of low-frequency guilt?

The Gowanus has suffered the pollution of both industrialized and post-industrialized New York—factory by-products, sewage, and food packaging—a conclusive list would quickly come to sound insane, like the rants of a muttering paranoid. Royte wisely takes the problem on via waste categories—following the garbage and recycling trucks to distribution centers, evaluating the success of various efforts at composting, landfilling, and burning trash. Royte writes a collective confession of New York; she illuminates the sins of simple city living, in which everything you use is hauled in huge machines to and from your door at enormous economic and environmental expense.

Royte cuts a compelling figure for the modern American left— one of the recurring images of her book finds her on the floor of her kitchen, weighing and meticulous recording the contents of her trash, before she chases it out into different areas of the waste disposal industry. She makes herself over as a detective crusading against the environmental guilt that now accompanies the most basic purchases.

Consumption guilt became, through the first decade of the 21st century, one of the most compelling motivators in contemporary American politics and culture. Famously, Naomi Klein argued in No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies (1999), that anti-consumption and point-of-consumption protest was the most vital way to effect change in the post-industrial First World. Klein’s ideas require a particularly enlightened thinking, in which left-liberals conceive their “interests” beyond the luxury commodities offered by global capitalism.

The “Occupy” protests, of which Klein has been a vocal supporter, take a different approach. The appeal of slogans about the “99%” depend on the near universal experience of some form of dispossession, of having one’s economic interests trampled by large-scale financial organizations. The fragile coalition built around #OWS draws together people whose 401ks have shrank (sometimes to nothing), whose homes have been foreclosed, and whose jobs have been outsourced. I submit that the guilt which defined consumption habits of the 2000’s plays an important role in knitting together the various interest groups which have been drawn to #OWS.

People like to refer to certain places as particularly unattractive parts of the body: cities or corners of them are said to be the armpit or the asshole, for instance, of the state or nation in which they lie. The Gowanus certainly calls to mind shameful orifices. But New York, the media capitol, the money capitol, always seems to me like a kind of eyeball, or insectoid array of eyeballs, into which fly images, things, animals, and people. And thus Gowanus must be an eyelid, soft orbic tissue, pierced and infected by a series of splinters.

The Gowanus as a crime scene is a kind of cold case, and yet the zeitgeist is palpable all along it. When we floated over towards what turned out to be a Port Authority installation, and a uniform came out and told us to move, “It’s a Patriot Act thing, guys, I got to ask you to paddle over there…” We tried to paddle into New York Harbor, so we could see the city in full, but we gave up while watching the head of the Statue of Liberty and the tops of the tallest skyscrapers peeking over the riverfront. Royte points out that rising sea levels could cause the polluted canal to flood over into surrounding neighborhoods.

I’ve probably been unfair in my thinking towards the girl at the party over the past decade. After all I’m the one who, as a full-grown adult, paddled into an environmental catastrophe, making jokes like “Superfund means SUPERFUN!” That I learned to love the city’s ugliness over the years, that I spent the intervening decade training my taste for its sublime rot, makes little difference between us, and even less of a difference for the canal. Especially in the face of all that filth we’ve made, which I recommend you check out for yourself. You’ll see a catalogue of the city’s sins carved out of the earth on which it’s perched, all the indifference of progress, every Styrofoam and plastic, every unpronounceable industrial chemical coming home to roost in a slowly swirling pool of guilt.