PAST ISSUES

Dr. Dame Daphe Sheldrick, founder of The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and author of "Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story", feeding an orphan elephant a special formula she created to keep orphaned infant elephants alive during their first crucial year.

Dr. Dame Daphe Sheldrick, founder of The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and author of "Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story", feeding an orphan elephant a special formula she created to keep orphaned infant elephants alive during their first crucial year. Elephants playing soccer at The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya as part of their exercise program.

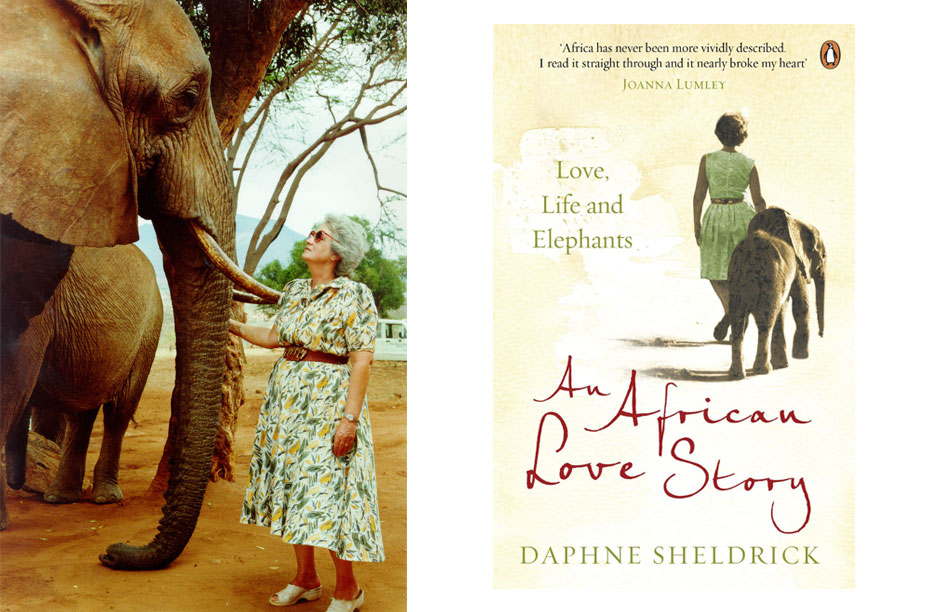

Elephants playing soccer at The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya as part of their exercise program. Image Left: Dame Sheldrick with her friend Eleanor. Image Right: The cover of "Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story", Dame Sheldrick's personal memoir.

Image Left: Dame Sheldrick with her friend Eleanor. Image Right: The cover of "Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story", Dame Sheldrick's personal memoir. Image by Robert Carr-Hartley

Image by Robert Carr-Hartley

Great Dame

By Kristan Schiller“For the first three years of life, infant elephants cannot live without milk,” explained Dr. Dame Daphne Sheldrick D.B.E during an interview at the Museum of Natural History in New York just before her book signing of Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story (2012), her memoir about her lifelong commitment to wildlife conservation and the enduring love she shared with her late husband David Leslie William Sheldrick MBE.

Dame Sheldrick, born in Kenya in 1934 to pioneer parents, was raised alongside animals, both wild and domestic. From 1955 until 1976, Sheldrick found herself surrounded by animals again when her husband became warden of Tsavo East National Park, a game reserve in Kenya, which is now the largest National Park in the country. In the early days, much of their efforts beyond expanding and maintaining the park went to fight off armed poachers who were seeking elephant tusks for profit. As a result the Sheldricks were placed in the center of an expanding crisis with the fallout being a growing population of elephant orphans. Tsavo soon became the epicenter for rehabilitating and protecting elephants in Kenya.

During her years with David at Tsavo National Park, they were unable to successfully raise an orphan younger than one year because they couldn’t find the exact formula that matched an elephant mother’s milk. “We’ve learned over the years and lots and lots have died and with every one that dies we do postmortems.”

After twenty years at Tsavo East National Park, the couple finally discovered the right mixture that could keep a baby elephant alive and in fact, says Sheldrick, help it grow and thrive. It was a combination of human baby formula and coconut milk, which helped keep a three-week old orphan elephant named Aisha alive. Tragically, Aisha died of grief months later when Sheldrick left her with an assistant to travel to Nairobi for her daughter’s wedding preparations. Then six-months old, Aisha thought she’d lost another mother when Sheldrick left temporarily, and stopped eating.

“Elephants are very human animals, emotionally. They are in some ways better than us,” says Sheldrick. “I always say it takes two years to make an elephant in the womb and nine years to make a man. That puts it all into perspective.”

Sheldrick said she learned a vital lesson in those early years, particularly with Aisha. Elephant families, she explains, are highly sensitive. Young elephants are raised in matriarchal groups with a doting mother, sisters, cousins and grandmothers – these bonds lasts a lifetime. Sheldrick says she grew to understand that in the orphanage she mustn’t let an elephant become too attached to one person. This is why the “keepers” at the orphanage rotate shifts with each elephant.

When David died suddenly of a heart attack in 1977, Dame Sheldrick carried out his legacy by founding the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and the David Sheldrick Elephant Orphanage in Nairobi National Park. Here, she still lives and works with her daughters Angela and Jill to try to rescue orphaned elephants whose mothers have been savagely killed.

To date, the David Sheldrick Elephant Orphanage has hand-reared as many as 67 infant African elephants whose mothers have been killed by poaching, war and disease with their personally-perfected infant milk formula. In 2006, Queen Elizabeth appointed Sheldrick a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire for this accomplishment. It was the first knighthood to be awarded in Kenya since the country received Independence in 1963.

Often called the “gentle giant,” elephants once roamed the earth in large numbers, tracing primordial migratory routes ingrained in their remarkable memory. Today, when elephants are not being slaughtered for their ivory or as bush meat, they are dying off from loss of habitat due to human encroachment and drought.

Sadly, Sheldrick paints a rather bleak future for her beloved African elephants. She says that poaching is now “beyond the capacity of local governments to control” because of the high price ivory brings. The price poachers get from ivory has gone up 50-fold in five years: from 300 Kenyan shillings a kilo to KS15,000 a kilo. CITES, (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and an international agreement between governments) is supposed to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. In 1989, CITES approved a worldwide ban on ivory trade and levels of poaching fell dramatically while black market prices of ivory declined. However, in the last 15 years, several countries have attempted to overturn that ban. In 1999, Botswana, Namibia and Zambia were permitted to have an “experimental” one-time sale of over 49,000 kilograms of ivory to Japan and in 2008, another approved sale of 105,000 kilograms of ivory to China and Japan took place.

Sheldrick is critical. “CITES is supposed to regulate the trade in endangered species but it’s facilitating it by allowing ivory to be sold. It is proven that the illegal ivory gets laundered into the system,” she states emphatically.

The illegal trade in ivory is worse today in some areas than it was in 1989 when the ban went into effect. In March 2013, CITES recognized that the systematic monitoring of large-scale seizures of ivory destined for Asia is indicative of the involvement of criminal networks, which are increasingly active and entrenched in the trafficking of ivory between Africa and Asia. CITES also determined that poaching is spreading mainly as a result of weak governance and rising demand for illegal ivory in the rapidly growing economies of Asia, particularly China.

“Elephants have a lifespan of 70 years,” says Sheldrick, the hope and indignation in her voice both immediately apparent. “They are on the same intelligence level as humans. They grieve and mourn as deeply as we do. And they are killed for a tooth. It is simply not ethical.”

Those interested in helping keep an orphaned elephant alive by giving a donation towards fostering can email rc-h@africaonline.co.ke or visit http://www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org/asp/fostering.asp for more details.