PAST ISSUES

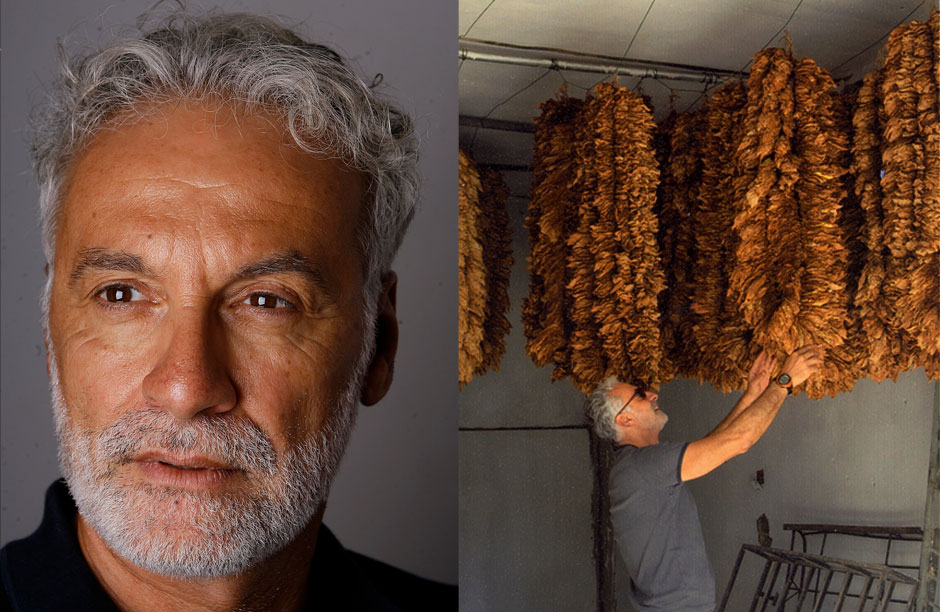

(Left) Portrait Rami Zurayk, author of "Food Farming, and Freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring" (2011) and founder of the Association for Lebanese Organic Agriculture and Slow Food Beirut, is a spokesperson and advocate of the slow food movement in Lebanon. (Right) Zurayk in southern Lebanon checking the tobacco harvest after the 2006 war. Photo by Anna Sussman.

(Left) Portrait Rami Zurayk, author of "Food Farming, and Freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring" (2011) and founder of the Association for Lebanese Organic Agriculture and Slow Food Beirut, is a spokesperson and advocate of the slow food movement in Lebanon. (Right) Zurayk in southern Lebanon checking the tobacco harvest after the 2006 war. Photo by Anna Sussman. Farmer in the Beqaa Valley in east Lebanon - the center of Lebanon's most productive farmlands. photo by Al Akhbar

Farmer in the Beqaa Valley in east Lebanon - the center of Lebanon's most productive farmlands. photo by Al Akhbar Zurayk's work towards keeping local farms thriving has made him into a spokesperson for the land bringing him into the company of farmers, investors, and foreign policy makers where he must wear the right dress and speak the right words to unite them with his cause.

Zurayk's work towards keeping local farms thriving has made him into a spokesperson for the land bringing him into the company of farmers, investors, and foreign policy makers where he must wear the right dress and speak the right words to unite them with his cause. Speaking to a group in south Lebanon.

Speaking to a group in south Lebanon. Zurayk leading a training program for a woman's coop.

Zurayk leading a training program for a woman's coop. Zurayk meeting with stakeholders in a project in south Lebanon.

Zurayk meeting with stakeholders in a project in south Lebanon.

I speak for the salt of the earth

By Jackson Allers“We pledge allegiance to our gods in the morning

And we eat them when the evening comes”

-Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, during his eulogy to Egyptian president Gamel Abdel Nasser in 1970

BEIRUT – I found this two line verse of Qabbani in a chapter of Dr. Rami Zurayk’s book Food Farming, and Freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring (Just World Books, 2011). It describes a period in pre-Islamic agricultural history when Arab tribes would make statues of their deities from ripened dates – later eating the dates when they were hungry.

“This is the best use of a deity I know,” Zurayk writes in a chapter which goes on to ask whether the Slow Food movement founded by Carlo Petrini in 1986 is in fact turning into a new religious movement. It’s a sense of sarcasm that I’ve come to know and appreciate in the five years I’ve gotten to know the man, born perhaps out of the embers of civil war which have never really seemed to die out for a generation that came of age during that time.

Zurayk is a professor of Ecosystem Management at the American University of Beirut’s (AUB) Faculty of Agriculture, and the co-founder of the Association for Lebanese Organic Agriculture and of Slow Food Beirut. He’s spent the better part of 25 years focused on the declining Arab agricultural sector, its relationship to food security and the plight of the small farmer.

This year an organization he founded – Healthy Basket – celebrated its 10 year anniversary in Beirut. A direct farmer to consumer delivery service that spent years jumping through the hoops imposed by European organic produce certification procedures – a process he abandoned in the end – Healthy Basket has a store front, 4 employees, and for the last 8 years has sustained itself without any external aid. With a stable of 40 small farmers providing the variety of produce that most Lebanese thirst for, it has been a grassroots success story.

Zurayk is upbeat but realistic when he tells me from his university office, “We’ve made it work. But there are really only about 15 farmers that are significantly providing us with produce. The problem is – how many people at the end of the day does this really serve? Maybe in the dozens at most. This is the scale in which all of these operations actually work.”

In this case, the “operations” he is referring to are the agricultural developmental schemes, usually implemented with foreign aid money, that come in for short-term bursts but have no real long term plans for sustaining the growing efforts of small farmers. “Nobody comes back ten years later to evaluate these kind of projects. Believe me,” he tells me.

When I met professor Zurayk in 2007, he was stewarding a project called “Land and People” – which subsequently became the name of his widely read blog. The aim of the project was to travel across southern Lebanon in mobile clinics – “agri-clinics” – rehabilitating the livelihoods of small farmers whose entire means of production had been destroyed after the devastating 2006 summer war with Israel. There were three clinics in all that served some 600 farmers.

“Pumps, orchards, cooperatives that we’d helped set up from 2002 until the war started – everything was in ruins,” Zurayk explains. “We basically had to start from scratch again. Imagine – from a fledgling but vibrant system of small farmer initiatives and cooperatives with a newly minted infrastructure – gone in one month of bombing.”

In a three year period between 2006 and 2009, Land and People became obsolete as the farmers regained the basic functions of their agrarian life, and as other developmental organizations entered the fray. It was a chance for Zurayk to move on. As he has professed to me on many occasions, “I believe there’s no need to keep an organization alive for the sake of the organization. Once it has achieved its goal and its purpose, then it can be put to bed and you can move on to something else.”

Of course that didn’t mean that suddenly farmers in Lebanon were in a place of food security. In fact, Lebanon and the Arab world have, according to Zurayk, suffered from decades of ill-guided state agricultural policies, all of which has been compounded by the global markets that these states have willingly chosen to participate in. They are systems that Zurayk has spent years combating, mostly through non-governmental organization’s he’s set up to engage civil society actors to respond to the needs of Lebanon’s small farmers – limiting the funding coming from organizations and countries that he finds have acted dishonorably in the region.

As Zurayk told WBEZ (Boston) radio’s Food Monday segment last year, “People need food and usually will buy the cheapest food that is available. If wheat is imported cheaper and the local market buys wheat at that price, that leaves the local farmer to sell at a loss. This doesn’t make sense for people who are farming and they will usually leave their land and become the poor and the unemployed in the cities as a result.”

Indeed, that has been the trend in the Arab world for the last 40 plus years. In the 1950’s, nearly 70% of the population in the Middle East and North Africa were from rural areas. Today Zurayk says that number is around 30%. It is a huge population shift, made even more ominous by the fact that the Arab world imports 50% of the calories it consumes, and is perhaps the most food dependent region on the planet.

In early 2011, his analysis of how the food crisis of 2007-2008 would affect the Arab world was premonitory. As he and his publisher Helena Cobban, founder of Just World Books, were putting together the book that eventually became Food Farming, and Freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring, the Arab Spring was erupting. “It was erupting overwhelmingly in these countries where rural communities had been destroyed and rural livelihoods had collapsed because of the onslaught of western trade and aid policies,” Cobban explained. “This is exactly what Rami had been writing about in most of the initial book Food, Farming and Freedom, so his writing had a real relevance and immediacy.”

They decided to end the book with the appropriately titled chapter: “The Arab Uprisings.”

As he said in a video interview after the release of his book:

“Can you really be free if you’re hungry? Can you really be free if you are in need? Can you really be free if you are dependent on aid to obtain your daily food? Freedom is indivisible. You cannot have freedom if you do not have access to the main determinants of freedom. You cannot have freedom if you do not have dignity.”

What I think makes professor Zurayk’s analysis all the more potent is that he is a scientist held captive by the allure of grassroots agricultural activism, wholly uncomfortable with the confines of the office, the laboratory, or the desk. He is a practical theorist and has moved into the role of an academician looking to sway the decision-makers by authoring guidelines to address the need for food sovereignty in the Middle East and North Africa. It is, as he says, the second phase of his work and one predicated on guaranteeing what over 400 farmers’ organizations defined in the 2002 World Food Summit as food sovereignty: “the primacy of people’s and community’s rights to food and food production – over trade concerns.”

Zurayk will be heading to Rome in September to meet with representatives from other food sovereignty networks as well as with members of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations to discuss concrete ways of making this happen.