PAST ISSUES

Chinese civil rights activist Chen Guangchen became an international icon when the global community donned dark sunglasses and united their voices in a plea to set him free...

Chinese civil rights activist Chen Guangchen became an international icon when the global community donned dark sunglasses and united their voices in a plea to set him free... Chen Guangcheng in front of his former home in Linyi after serving four years in prison for organizing a class-action lawsuit against the city of Linyi for their harsh enforcement of China's "One-Child Policy"

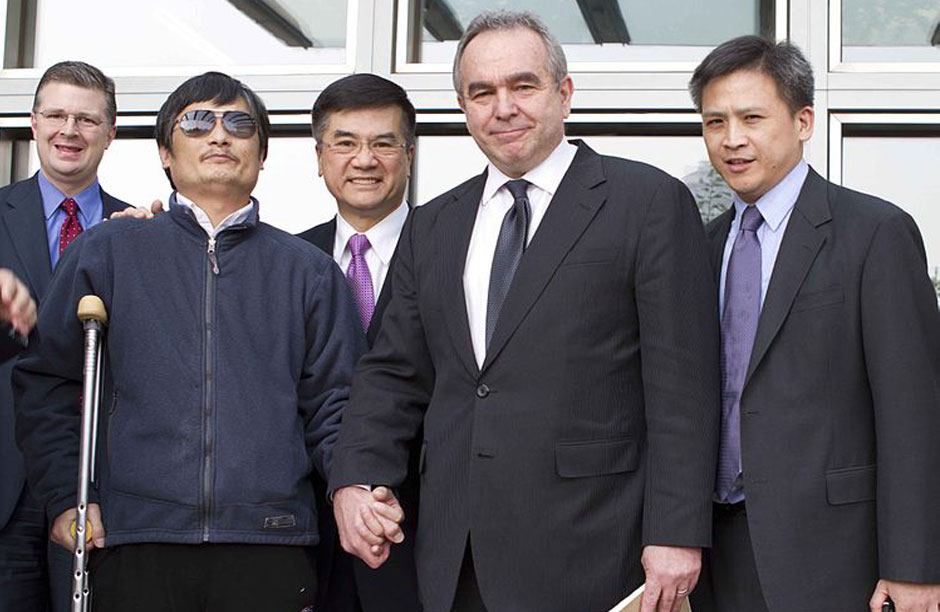

Chen Guangcheng in front of his former home in Linyi after serving four years in prison for organizing a class-action lawsuit against the city of Linyi for their harsh enforcement of China's "One-Child Policy" Chen Guangcheng arrives at the US Embassy in Beijing after 4 years in prison, two years under house arrest and continued harassment and physical abuse from Chinese government officials.

Chen Guangcheng arrives at the US Embassy in Beijing after 4 years in prison, two years under house arrest and continued harassment and physical abuse from Chinese government officials. Chen Guangcheng and his wife Yuan Weijing now live in Greenwich Village in New York City with their two children. Chen is currently a student at New York University School of Law.

Chen Guangcheng and his wife Yuan Weijing now live in Greenwich Village in New York City with their two children. Chen is currently a student at New York University School of Law.

Prisoner of Conscience

By Nathaniel SandlerThe story of the blind Chinese activist Chen Guangcheng is completely riveting. Upon his politically charged arrival in the United States via invitation from New York University’s Law School, it’s not hard to envision the film waiting to be produced. Speculating on the potential method of storytelling is an exercise in social consciousness. Does Hollywood have the stones to cast an Asian guy as the lead? If so, would it be mandatorily spiced up with super sexy cutting edge martial arts moves? One can’t help but make a perfunctory analogy to Zatoichi, the wildly popular Japanese blind swordsman character. Being an Asian Studies major at Vassar College, and someone who has lived and worked in Asia for the better part of last decade I know that this analogy is unfair despite being unfortunately mentally reflexive even for an American versed in Asian motifs. What Chen Guangcheng has been able to accomplish in China, and internationally, without his sight is nothing short of spectacular.

In 2006, Chen Guangchen was jailed for protesting against the use of forced sterilization and abortion in accordance with China’s One-Child policy. This is, on every possible level, a just cause. The central government in China holds local governments to child rearing quotas and in some rural areas of the country, like Chen’s home province of Linyi, the local bureaucrats have been known to resort to hard-handed and morally questionable tactics. He was jailed on trumped up charges relating to his vocal protestation of these methods. Upon his release 4 years later Chen was placed on house arrest during which his family was repeatedly harassed and even physically beaten on multiple occasions. Their possessions ravaged, and their morale destroyed, Chen decided to escape to seek help.

Picture the scene: a blind man crawls for 19 hours, scaling walls past sleeping guards with three broken bones in his foot due to a particularly taxing fall during his escape. The situation could be described as cinematic mostly due to its unbelievability. He then met with a young teacher and activist known as “Pearl” who drove him 300 miles to Beijing. Then, a series of rendezvous with complicit dissidents and their safe houses, eventually cleared a path to the U.S. Embassy. Strong armed tactics and posturing from the Chinese Government and U.S. alike eventually led to his arrival in New York on May 20th. Initially a deal was struck in which Chen and his family would stay in China and study law, but this was blown to pieces when he found his wife was being violently interrogated by Chinese officials while he was at the embassy. Someone please write this film. I am too enamored with the plot to be effective. Rumor has it, Chen is already shopping around for a book deal and movie could be in the pipes pretty soon.

What is ultimately interesting about Chen’s story is the subject of China itself and America’s relationship with her. The dance the two constantly enter can be an awkward one and it is no mistake that Chen ended up at the U.S. Embassy and not another open-minded western government’s safe house. Perhaps we are inextricably linked through manufacturing supply chains and a habit-formed unspoken dependence on cheap plastic stuff, but either way, China and the United States continue to grow unsustainably together. During this process, both sides allow the other the occasional ethical mulligan. The United States can muddle up the Middle East while wearing the sheriff of the world badge, and China can not so silently repress its own people. When the heavily polished shoe is on the other country’s foot they are much better at covering their own tracks. Still, the moment concerned Americans hear of an intriguing enough internal human rights battle in any country, the liberal base will at least feed the media machine. Chen’s story has conflagrated to the point of passive rallying and we want to watch the man succeed, yet both Governments lightly chide while understanding that domestic business is just that and no other nation’s concern.

Some of the more inspirational action heroes recently, like Chen Guangcheng or Ai Weiwei have come from China, ostensibly due to those in power and their unwavering willingness to mix it up with driven activists and thinkers, despite obvious breaches of human rights. Once, in Suzhou China I befriended an English speaking bar owner named Eric, who was heavy on scotch but keen on finesse at the pool table. After a week of coming in for a drink and listening, he offered to drive me to the train station on my way out of town. We piled my pack and myself on to his scooter and took the long way downtown while I got a brief tour of the land, what it was, and what it used to be. We came up to two of the biggest buildings on a main thoroughfare and my guide pointed to the left at a high gloss modern building and identified it as the university. Across the street sat a squat cement imposing brick building which he told me was the local jail. In a moment of rare and unadulterated honesty, Eric simply said, “if you get too many ideas in school, they just send you across the street.”

I’d like to think that Eric had the right sense of humor for the job of driving me to the airport, but certainly at the time he would not have made that joke to another Chinese. Perhaps the talk on this side of the supply chain should begin to reflect on our relationship with China in a constructive manner, instead of fear-mongering economic worries about the created shadow of China, or flippantly disregarding their human right’s record as appalling. And most importantly we should look to an inspirational figure such as Chen Guangcheng as a beacon, slowly crawling past those looming and damnable authority figures towards a different and universally acceptable freedom. Hollywood. Make this movie. It will help.