PAST ISSUES

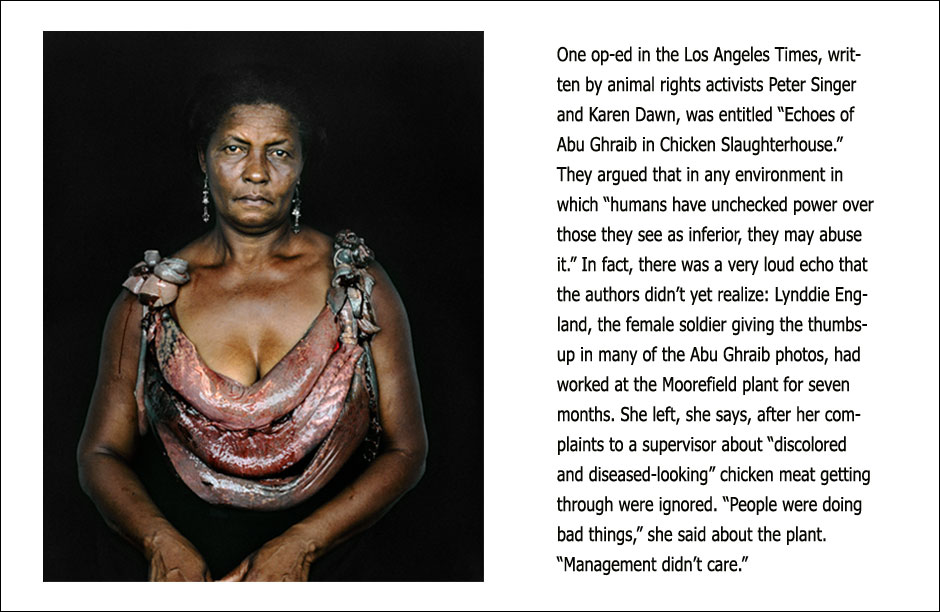

Image: Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled (PYM7.22)", 2007, C-print, 40" x 30", edition of 6. Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do".

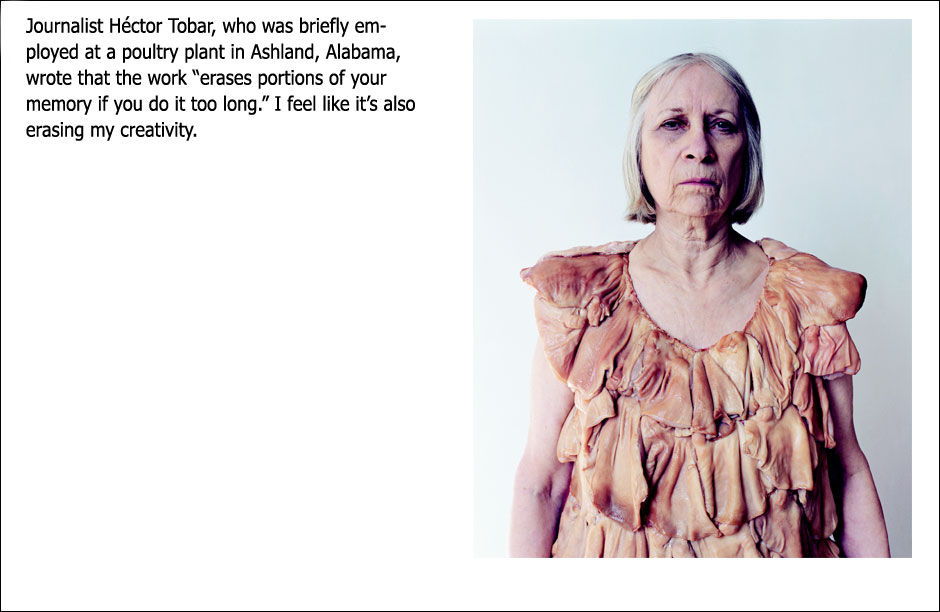

Image: Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled (PYM7.22)", 2007, C-print, 40" x 30", edition of 6. Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do". Image Left: Pinar Yolaçan, from “Perishables” (2004). Image Right: Pinar Yolaçan, from “Maria” (2007)

Image Left: Pinar Yolaçan, from “Perishables” (2004). Image Right: Pinar Yolaçan, from “Maria” (2007) Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled" (2002), C-print, 40" x 32 3/8". Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do".

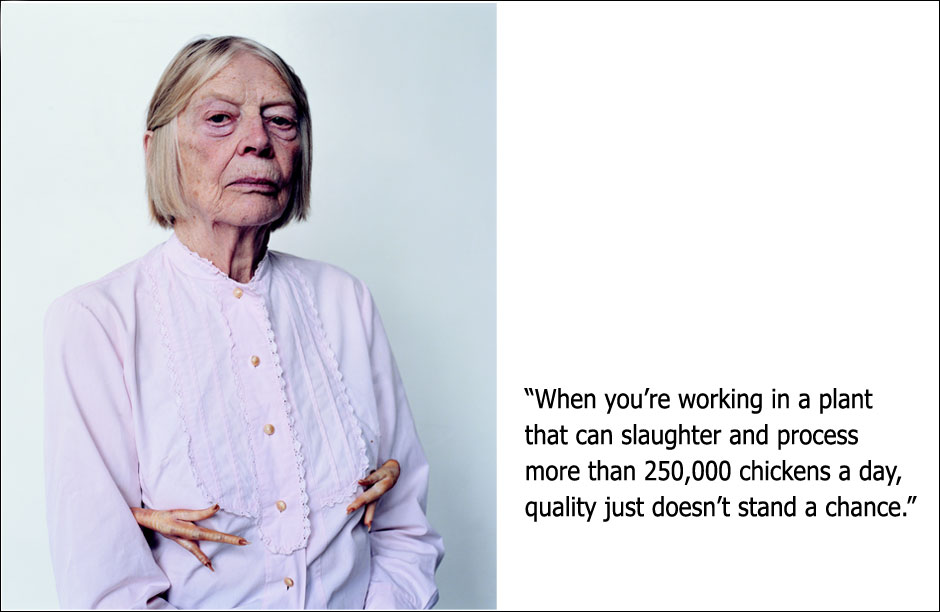

Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled" (2002), C-print, 40" x 32 3/8". Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do". Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled" (2004), C-print, 40" x 32 3/8". Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do".

Pinar Yolaçan, "Untitled" (2004), C-print, 40" x 32 3/8". Excerpt from Gabriel Thompson's "Working in the Shadow's: A Year of Doing The Jobs [Most] Americans Won't Do".

Working in the Shadows

By Gabriel ThompsonI set out to write Working in the Shadows after reading an article in the New York Times in the fall of 2007, which recounted the problems a hog slaughterhouse was having in retaining American workers after an immigration raid caused more than one-thousand Latino immigrants to depart. Many people in the article were astounded at how difficult the work was, describing nauseous conditions and swollen hands. By the time I finished the piece, the project was already forming in my head: over the course of a year, I would do low-wage jobs in industries dominated by Latino immigrants, and write about it.

One of the early lessons is that doing these sorts of jobs means learning to live in constant pain, especially in the hands and back. In the Arizona lettuce fields, each crewmember would cut 3,000 heads during a shift; in the poultry plant, line workers could make more than 18,000 cuts of chicken meat in eight hours. That’s the kind of work that leads to serious injury if done for a few years.

Another eye-opening experience was to witness the degree of rural poverty suffered by US citizens. The swelling in their hands required regular use of painkillers (the company kindly had a number of dispensers in the break room); the $16,000 a year meant that an economic emergency was always on the horizon. Early on, an African-American woman who worked near me was fired for falling asleep. She would simply tuck her chin into her neck and be out, without falling over. How she did that, I have no idea—but I did learn why she was so tired. It turned out that she had a young son, and though she found someone to watch him during the night (we worked the graveyard shift), she couldn’t afford a sitter during the day. After an eight-hour shift, she was home with a child who was just getting up and ready to play.

Witnessing such events underscored how this book wasn’t so much about immigrants as it was about the situation of invisible workers who we all rely upon but rarely hear from. The Americans and immigrants I met had much in common—for one thing, they are equally ignored in the stump speeches of politicians—and despite the lack of a shared language, in many workplaces a sense of solidarity could develop, if only because each group harbored equal disdain for their supervisors.

The following passages are excerpts taken from the book Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won’t Do by Gabriel Thompson. Excerpted by arrangement with Nation Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2010.

I.

For the first time I’m able to take in my surroundings. To my right is the re-hang area. It is called re-hang because it is the second time the birds are hung up: The first is in “live hang,” where workers grab live chickens that have been delivered by truck and hang them upside down on metal hooks. Once attached, the heads of the live birds pass through a tank of electrified water, rendering them immobile. They are then beheaded by a mechanical blade and submerged in boiling water to remove their feathers. When the process works correctly, the chicken becomes unconscious upon hitting the electrified water and is killed by the blades. But, as anyone who has worked in a chicken plant knows, the scale and pace of the operation means that the system rarely operates perfectly. When the water isn’t sufficiently charged, the birds remain conscious for the beheading phase. When the mechanical blades miss the chickens’ necks, a group of workers known as “kill room attendants” or “backup killers” are on hand to manually slit the birds’ throats. Still, each year millions of birds somehow survive the bath and various blades and are boiled alive. Now dead and de-feathered, the chickens enter the evisceration phase. One way to envision what happens in evisceration (or “Evis,” as it is called at the plant) is to read through the job titles, which range from neck breaker and oil sack cutter to giblet harvester and lung vacuumer. Workers stand one next to the other as the birds fly past, each doing their part until, by the end of the line, the result is a disemboweled carcass that stick their hands into the pile of moist chickens, grabbing carcasses by the legs, and slide what I guess are the chicken’s ankles through metal hangers that pass quickly at forehead level. After one bird is hung, they immediately stick their hands in the pile of chicken for another; in re-hang there is no time for breaks. Squirrel has been at the plant for many years and previously worked in re-hang. He’s glad to be out. “You have to hang twenty-eight birds a minute,” he says, joining me on a nearby cardboard box. “They will stand by you with a stopwatch to make sure. When you first start, it tires out your shoulders, until you get used to it.” Indeed, at the moment there is a supervisor’s assistant—identifiable by his blue hairnet—walking back and forth in front of the workers, pausing occasionally to assess an individual’s output.*

II.

BEFORE FALLING ASLEEP back at my trailer, I take stock of my first two weeks as an employee at the plant. I’ve met one woman from orientation now working an eighty-hour week to support her family. Another mother, exhausted because she can’t afford childcare, is fired after being unable to stay awake while separating chicken strips. Now my neighbor has nearly killed himself because he didn’t have enough money to pay for an air conditioner. I don’t consider myself naive when it comes to poverty. I know millions of people struggle every day for things I take for granted. I spent five years organizing tenants on the brink of eviction in Brooklyn, and another three years reporting on issues related to poverty. But I’m still not prepared for what I’ve encountered in Alabama. I’ve come to write about the lives of immigrants but have been blindsided by the degree of rural poverty suffered by U.S. citizens. I am reminded of how Barbara Ehrenreich characterized poverty in Nickel and Dimed. Forget about poverty as something sad but sustainable, she argued; instead, poverty must be recognized as “acute distress” and “a state of emergency.” The grinding, deadening work; the workplace diet of sodas and candy bars; the sleep deprivation; the frequent health emergencies; the complete lack of savings: Unsustainable is one of the first words that come to mind when I consider the lives of my Englishspeaking coworkers. (The immigrants in the plant seem better off—both mentally and physically—probably because they can favorably compare the wages and working conditions to what they have left behind in Guatemala.) To understand the nature of the distress, it helps to have access to the facts of their lives—to know about the car driven into a ditch and the son who wakes up just as a mother is ready to collapse. But the presence of distress is a more public affair: It is written across each face. The first thing an outsider at the plant will notice—it is impossible not to—is that every American worker over forty is missing some front teeth; and the gummy smiles, combined with the thick creases that carve up cheeks and foreheads, make people look decades older. I often felt, on learning someone’s age, that I had been transported back to the harsh frontier life of the early 1800s. An overweight, gray haired man with a bent back and chronic cough, who I imagine must be nearing retirement, turns out to be forty-two. Before I can catch myself, I think: He probably won’t be alive in a decade. “Working the night shift makes you old quick,” Kyle tells me. I won’t be here long enough to feel its full effect, but my lack of premature aging is regularly noted. I’ve never been told that I look particularly young for my age, but at the chicken plant people are genuinely astounded when I tell them I am thirty years old; everyone assumes I recently graduated high school. Some people refuse to believe I am telling the truth after I insist upon my age. “If you don’t want to tell me your real age you don’t have to,” one woman laughs, before asking me for the second time what I have to hide. I eventually say that I am twenty-two just to change the subject. I have felt fortunate for many things—economic stability, access to a college education, work that I enjoy—but it’s never occurred to me to be thankful for the sum of all these good fortunes: Life isn’t “making me old quick.”

* * * *

Finally, one of the last lessons learned was that, at the bottom-rung of the economy, undocumented immigrants aren’t taking jobs from Americans. In each place I landed, I quickly found work. The difficulty wasn’t in getting the jobs—the difficulty was in surviving the jobs. And the challenge now is to transform these jobs into ones that aren’t so hard to endure.