PAST ISSUES

ISSUE No.1 WATER

In our premier issue we start with the source of all life: water. The Water Issue travels to the ends of the earth and beyond - from Central Africa, to Sweden, to the Palestinian Territories, and even into Outer Space. A movie producer takes a break from the high stress world of Hollywood to learn to surf - a 1 week vacation turns into 1 year as she becomes a student of water the "greatest teacher I have ever known" - Philippe and Alexandra Cousteau share the Legacy of their grandfather's love for the ocean - the obsession with bottled water falls under scrutiny...and more.

High dive into Lake Malaren, downtown Stockholm.

High dive into Lake Malaren, downtown Stockholm. Fishing off of the main square in Stockholm is still a common pastime.

Fishing off of the main square in Stockholm is still a common pastime. R.C. Jah explains the Sulabh Public Compost Toilet System designed by Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak, winner of the 2009 Stockholm Water Prize.

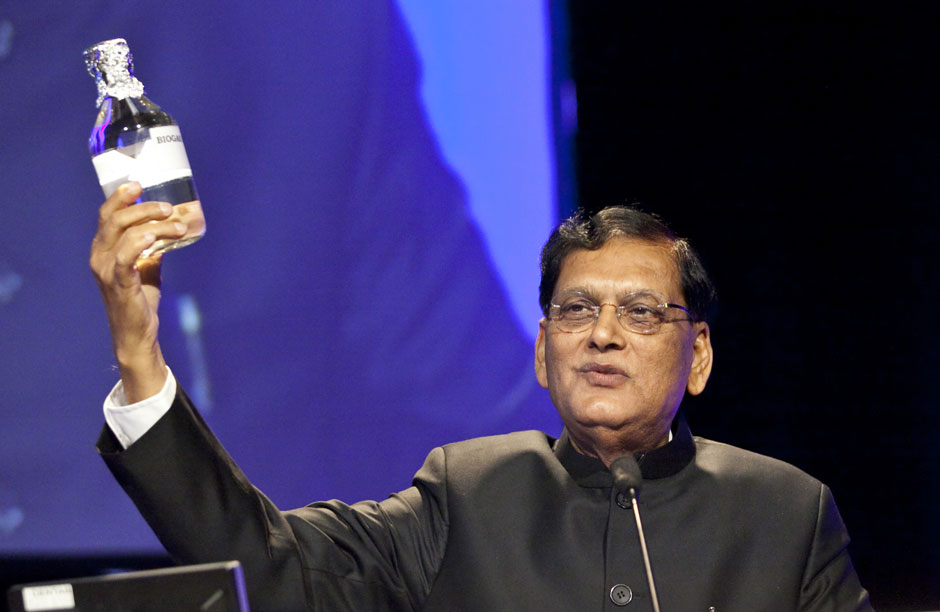

R.C. Jah explains the Sulabh Public Compost Toilet System designed by Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak, winner of the 2009 Stockholm Water Prize. Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak of India, winner of the 2009 Stockholm Prize for his innovation in public sanitation.

Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak of India, winner of the 2009 Stockholm Prize for his innovation in public sanitation. A young boy jumps into Lake Malaren near downtown Stockholm.

A young boy jumps into Lake Malaren near downtown Stockholm.

Sweden, the Model (Green) Citizen, is Giving Away Prizes

By Lotta Zachrisson and Lisa OlssonWhen it comes to the environmentally conscious, if thinking on a global scale, there are a few countries that sit on a high ledge in order to serve as models to the rest of the world. Sweden, according to a 2008 Yale study, is number three on that list. (FYI: The U.S. made slot 38). Earlier this year Stockholm was the first city to be named “European Green Capital”. One of the main reason’s for the honor was the 2006 Stockholm Water Programme adopted by the Stockholm City Council to reach higher clean water standards. And, when it comes to water, Sweden can boast a special bond to the life sustaining element.

The first thing that strikes you when visiting Stockholm is how the city is literally built on water. There are 50 bridges hovering over lake Malaren and the Baltic Sea to connect 14 different islands that make up the city’s center. What’s more striking, is that all of this water, even in the middle of the city, is clean. People can swim almost anywhere, even from the steps of City Hall, and one of the most popular spots for fishing is close to the congested Royal Palace in Stockholm’s Old Town.There is no doubt that the city has been privileged in its location.

There are plenty of lakes and rivers in the surrounding areas, and the rainfall and melting ice ensures that there is no lack of fresh water. To further tip the scales, the population is relatively very small.

And because Stockholm has been blessed with a bounty of natural resources, it has been possible to concentrate more on environmental thinking, something that you can see in various ways around the city. Many people are taking their bikes to work or using the public transportation system – the subway and inner city buses – which all run on renewable fuels.

A new residential area, Hammarby Seafront, is built just by the water as an example of how urban life can be integrated with the environment – a model within a model. The houses are better insulated to minimize use of electricity for heating, and all the garbage is being recycled, even the food waste, which is thrown away in compostable bags made out of corn that the residents can pick up for free in local shops. The mindset is to, like nature, recycle waste into something productive. For example the sludge in the water

treatment plants are being converted into biogas.

In continuation of Sweden’s commitment to environmental leadership, we are also the host of World Water Week, the most important international conference on water issues, held every year in August. Since its inception in 1991, it has grown from a meeting of only about 100 delegates to an estimated 2,500 people from 130 countries. At World Water Week, scientists,environmental politicians, United Nation’s officials and NGOs meet to discuss a range of water issues, share experiences and to get inspired by how other countries have solved their water related problems.

Cecilia Martinsen, director of the Stockholm International Water Institute, SIWI, and the organizer of World Water Week, explains that WWW actually started casually, with the travel and tourism sectors deciding to throw something called the Water Festival. Apart from a big event with culture and food, they decided to include a water prize to reward important work in the field. There is also a Junior Water Prize for a winner between the ages of 15-20.

The Stockholm Water Prize is now one of the highlights of World Water Week. This years’ winner, Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak from India, was awarded (150,000 USD) for his work with human rights in the sanitation field. In 1970 he started the organization Sulabh, which has developed a cost effective toilet system for use throughout India’s poorest communities. His goal is to end the use of “scavengers” – people who manually clean human waste from bucket latrines – and as a result often die from bacterial diseases. “When I started it was only me who went from house to house, ” Dr. Pathak explains. Today Sulabh has 50, 000 people working alongside Dr. Pathak. He continues, “In 1970 there were 3 million scavengers in India, but now there are only about 100, 000 left.”

The scavengers are always from the lowest caste – the “untouchables” – and Dr. Pathak has also fought for their liberation from the caste oriented social system, which still holds firm in rural India. “The untouchables don’t exist in law but socially they still do,” says Pathak. He feels that all disparate political parties in India should at least unite on the issue to banish the caste system once and for all. And, somehow by way of a toilet, that is what Dr. Pathak himself has done.

The toilets from Sulabh now exist in 1.2 million private houses and there are more than 7,500 public Sulabh toilets used by 10 million people daily. The toilets only need 1.5 litres (approx. a quarter of a gallon) of water for flushing compared to about 10 litres (approx. 2.5 gallons) for ordinary toilets. “This is extremely important in water-poor regions”, Dr. Pathak says. He has also come up with a technology that converts waste into biogas, which can in turn be used for electricity, heating water and cooking. And so, in India, as in Sweden, frugality with natural resources is being practiced. One out of necessity, and the other out of a prescient respect for the necessity of the next generation.

In all fairness, I am a native Swede, and I can attest that we are not perfect. In Sweden the sorest spot is without a doubt the Baltic Sea. As an inland sea it has a very sensitive ecosystem and the biggest problem is nutrient loading – a result of farming practices in the surrounding countries. The Baltic Sea borders with 9 countries (Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany and Denmark), but even though it is often heard that coal burning countries like Poland or the Russian area of Kaliningrad are to blame, according to Jakob Granit, a specialist on the Baltic Sea from SIWI, this is not true. “Sweden is very much at fault,” Granit explains, “Sweden and Denmark have very modern farming methods, which use more nutrient-rich artificial fertilizers. “Nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen leak from Swedish farmlands into the Baltic. The real evidence lies in our geography, “Sweden has a very long coast, so a lot of it is coming from us,” says Granit.

The nutrient build up in the water leads to algal bloom, which decreases oxygen in the water. At its worst, the water is no longer swimmable because of the outcrop of poisonous blue-green algae, while fish and marine life have inevitable been effected.

So how does the world’s number three environmentalist find themselves in such a predicament? The important thing to watch is how we get out of it. As Churchill said, “The price of greatness is responsibility”. It also doesn’t hurt to seek out help.

Sweden is working with all the EU countries bordering the Baltic to solve the problems facing its waters. The strategy includes an action plan with 80 micro projects. One such project, for example, is to develop energy crops, which are capturing the nutrients that would otherwise end up in the sea.

Sweden might be a country to envy and admire at the moment, but only 30-40 years ago the situation was quite different. It is what we have done since then that has made all the difference, just as we are doing right now about the Baltic Sea will show in the future. The truth us, it’s never too late to start the work, and it can be done on so many levels – city planners can put environmental issues at the top of their lists, politicians can install incentives for greener choices and everyone can make small decisions about their own use of public transportation and how much waste they produce. If you ask Stockholmers about the clean waters and green areas surrounding their city you will realize that many of them take great pride in those things. That is the secret, when people really care about their local environment they will do something to protect it.