PAST ISSUES

ISSUE No.1 WATER

In our premier issue we start with the source of all life: water. The Water Issue travels to the ends of the earth and beyond - from Central Africa, to Sweden, to the Palestinian Territories, and even into Outer Space. A movie producer takes a break from the high stress world of Hollywood to learn to surf - a 1 week vacation turns into 1 year as she becomes a student of water the "greatest teacher I have ever known" - Philippe and Alexandra Cousteau share the Legacy of their grandfather's love for the ocean - the obsession with bottled water falls under scrutiny...and more.

Ancient burial mounds in Bahrain - once the purported site of the "Garden of Eden". Scholars have documented that the ancient peoples buried there believed their bodies would be returned to Paradise if interred within that soil.

Ancient burial mounds in Bahrain - once the purported site of the "Garden of Eden". Scholars have documented that the ancient peoples buried there believed their bodies would be returned to Paradise if interred within that soil. Aerial view of the burial mounds of Dilmun (Eden) in Bahrain

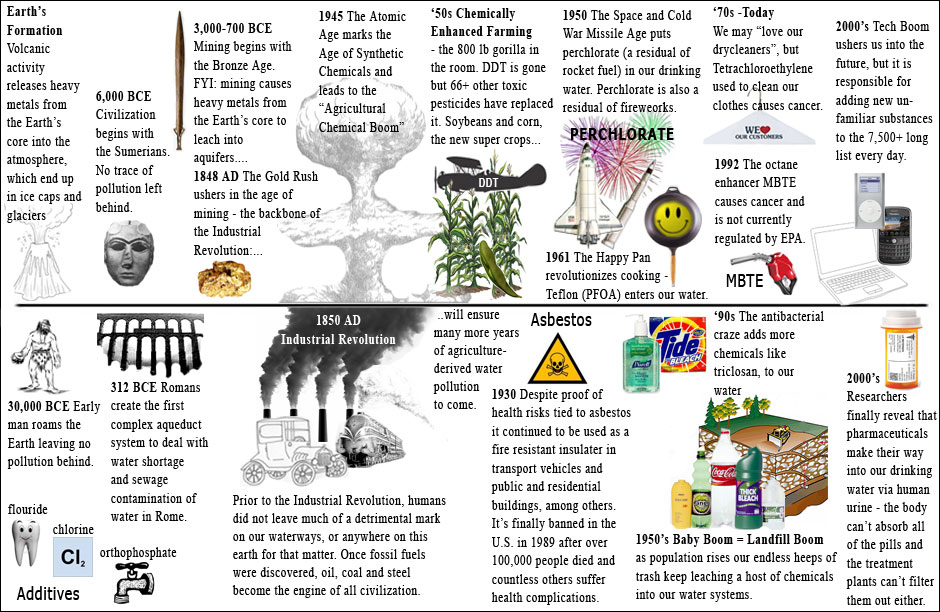

Aerial view of the burial mounds of Dilmun (Eden) in Bahrain A timeline of water's fall from Paradise.

A timeline of water's fall from Paradise. Al Hidd desalination plant in Bahrain produces 90 million gallons of water per day. According to the International Desalination Association, the Middle Eastern region of the world is responsible for 75% of the total global production of desalinized water.

Al Hidd desalination plant in Bahrain produces 90 million gallons of water per day. According to the International Desalination Association, the Middle Eastern region of the world is responsible for 75% of the total global production of desalinized water. The Author, Hayfa Matar, tests a sample of water at the Ras Abu Jarjur desalination plant in Bahrain.

The Author, Hayfa Matar, tests a sample of water at the Ras Abu Jarjur desalination plant in Bahrain.

Return to Paradise

By Hayfa MatarIf you live in Bahrain, as I do, you know what it’s like to live on a small island – to be surrounded by water – and to experience the surreal humor of being faced with the problem of water shortage. You would also know that Bahrain is the mythical location of the Garden of Eden. Near the town of Madinat Hamad there spreads an ancient burial site, a maze of dirt mounds blistering the landscape. In these sandy graves lie the remnants of ancient people whose kin traveled for miles to return their bodies to the soil of paradise.

An excerpt from one of the oldest poems, written circa 4,000 years ago in the ancient Sumerian city of Nippur, sheds light on the legend behind our present day island necropolis:

“Dilmun is holy, the land of Dilmun is pure. In Dilmun no cry the raven utters, Nor does the bird of ill-omen foretell calamity… The somber death priest walks not here, By Dilmun’s walls he has no cause for lamentations.”

This description of Dilmun, the ancient civilization associated with the archipelago of Bahrain, bears resemblance to the features of the Garden of Eden, a paradise where Adam and Eve lived in harmony with all creatures, where sweet water flowed continuously and where life was eternal.

Although the location of the Garden of Eden remains contested, many claim that the land of Dilmun (Bahrain) was its location.

In fact, historically, Bahrain was an oasis, covered by date palm trees and freshwater springs in the reefs. Spring water was so abundant that inhabitants used to dive and fill bags of water from the sea for drinking. Now Bahrain is part of the desert region that harbors and supplies 60% of the world’s total oil reserves, thanks to its fertile, tree-laden past. The irony extends even further when you calculate the 75% cost leverage that very same oil provides to Bahraini’s in order to create clean, potable water out of the salty waters of our sea by the method of desalination.

Desalination is the most expensive method of water purification that exists today, and it is the main water treatment method used in Bahrain. Bahrain had once relied on other water supply options, but these were contingent on natural renewable sources, often unpredictable, and with finite availability. Most of Bahrain’s freshwater aquifers have been contaminated by seawater after pressure from several bore hole sites lowered the freshwater table below sea level. This is an all too common occurrence in coastal and island regions throughout the world. The prospect of desalination instantly increases a coastal community’s water supply, and thus is a water treatment solution that is gaining wider popularity.

All the water we drink is treated. Even “clean” water from lakes and rivers needs to go through a rigorous process to make it safe to drink. When water is being “treated” it is essentially going through a process of subtraction (of impurities) and addition (of chemicals). Treated water around the world is dictated by a set of standards created and approved by each nation’s government. Every country varies in their drinking water standards. In Bahrain the standards are set by the Word Health Organization. The Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration, both agencies of the U.S. government, set the standards for drinking water in the United States.

Under the auspices of the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (1976), the EPA requires every municipal water treatment plant in the U.S. to test for, regulate and publicly disclose the levels of 88 contaminants. It is important to note that these “safety levels” are determined according to the weight of a 150lb adult. It is also important to note that there are an additional 116 unregulated contaminants waiting to be passed for regulation that were selected by the EPA from a list of upwards of 7,500 potential contaminants identified by researchers to be present in our drinking water.

THE HIDDEN MESSAGES IN WATER

The 204 regulated and unregulated contaminants that have slipped into our drinking water came from a wide range of sources. Water is like a great mirror reflecting back to us who we are. The history of man’s activities can be traced in the contaminants found in our water. The magical thing about water is that it is the most tolerant substance in the world – which means it will embrace anything that comes into contact with it, and seemingly erase it. This last trait is the dangerous part. Water is so good at what it does, that it often renders the deadly toxins it carries, untouchable, invisible, scentless, and worst of all, tasteless. As the human population proliferates, industrial and technological production mushrooms, and less and less freshwater is available, the freshwater that is available continues to become more and more polluted with dangerous impurities.

To rid water of these toxins several methods have been devised. The most widely used water treatment method is chemical treatment. The chemical of choice is chlorine. Chlorine was discovered by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1784, and its first practical use was to bleach textiles. The safety of chlorine is contingent on balance. In World War I the German’s debuted chlorine gas as a weapon to kill. While in 1901, the United States initiated the widespread use of chlorine for municipal drinking water to combat a deadly outbreak of cholera.

I honestly hadn’t thought too much about water purification before. I took my drinking water for granted. The first thing I decided to do when I took on this assignment was visit a desalination plant and see the process for myself. On a Tuesday I arrived at the Ras Abu Jarjur Desalination Plant. First off, I was overwhelmed by its size, and keep in mind, it is now one of the smaller plants on the island. When one thinks of clean water, a mammoth industrial plant is not the first thing that comes to mind. I was scheduled for a tour and an interview with Dr. Abdulmajeed Al Awadhi, Chief Executive of the Electricity and Water Authority in Bahrain.

There are two processes of desalination: Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSF) and Reverse Osmosis. MSF, the preferred method in Bahrain, requires multiple stages of treatment, which starts out with boiling seawater to create water vapor. The sounds of all the processing pumps and filters were deafening. I kept wondering whether a noisy environment can affect the taste of water – I suspect it does.

After the tour they led me to the plant’s laboratory, which was rather small and in a state of disarray. They handed me a glass and laid before me a few blind samples. I brought the glass to my nose. I could not detect any distinct odor to the water. I then took a sip. I felt that it had a very slight mineral taste, but I could not detect any salinity. I was surprised to discover from the lab technician that in spite of how subjective our sensory perceptions may be – the satisfaction or dissatisfaction they cause in each individual – they are nevertheless a key pillar for water research.

During our interview, Dr. Abdulmajeed Al Awadhi informed me that 90% of Bahrain’s drinking water comes from desalinized seawater, the other 10% from freshwater aquifers. He explained, “The process of desalination does not produce the right combination of salt. We therefore need to mix the water from desalination with 10% of water from aquifers for it to become “good” water. Hence, we need aquifers for that 10%.” This had me thinking about environmental sustainability. He explained that he could not account for the effect, if any, on sea life because the evidence of damage to sea life caused by the pumping and dumping of desalination plants has not been documented and disclosed at this point. Dr. Al Awadhi did admit that the gas and oil needed to power the desalination plants add a significant amount of carbon dioxide to the environment, but as Bahrain takes cues from the neighboring United Arab Emirates, he has high prospects for the implementation of emerging technology such as nanotechnology and cutting-edge renewable- energy resources.

Dr. Al Awadhi was very clear on the tremendous financial expense of desalination. If the plants, the research facilities, and the energy required to power the process of desalination are not economically sustainable, how applicable is the method of desalination to developing countries – where the untreated drinking water supply is the cause of 80% of all illnesses?

I was encouraged, during my research of this issue, when I came across the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems in Freiburg, Germany, which developed solar thermal desalination plants that can help poor countries transform seawater or brackish water to pure drinking water at a low cost. Yet, I remain convinced that, although the price of desalination will likely decrease with future technological research, it is highly likely that it will continue to play a salient role in affluent coastal countries scarce in water resources, but highly unlikely that it will assume a paramount role in developing countries.

Dr. Al Alwadhi surprised me when he added his perspective to this debate, “The water is subsidized by 75%, therefore people only pay 25% of the cost of water, this is because the source of energy (gas and oil) is heavily subsidized. This causes problems in awareness, conservation, accountability and responsibility. The best way to increase awareness is to increase the price of water.”

Is that what it really would take for us to appreciate and conserve the resource that keeps us alive? Many conservationists agree with this approach. “Money talks”, as they say, and it may very well be the voice to awaken each of us. I still cannot take my sights of the issue of equality, and the basic human right to life, which could not be available to all without clean water. The way I see it, unless we invest in preventative measures such as the establishment of an international organization dedicated solely to managing global water resources and enhancing our conservation efforts globally, our future military conflicts will be fought over water, and any remnants of the Garden of Eden will evaporate forever.