PAST ISSUES

Noel Grundwaldt, "Untitled #20, 2008". Courtesy Stellan Holm Gallery Gallery

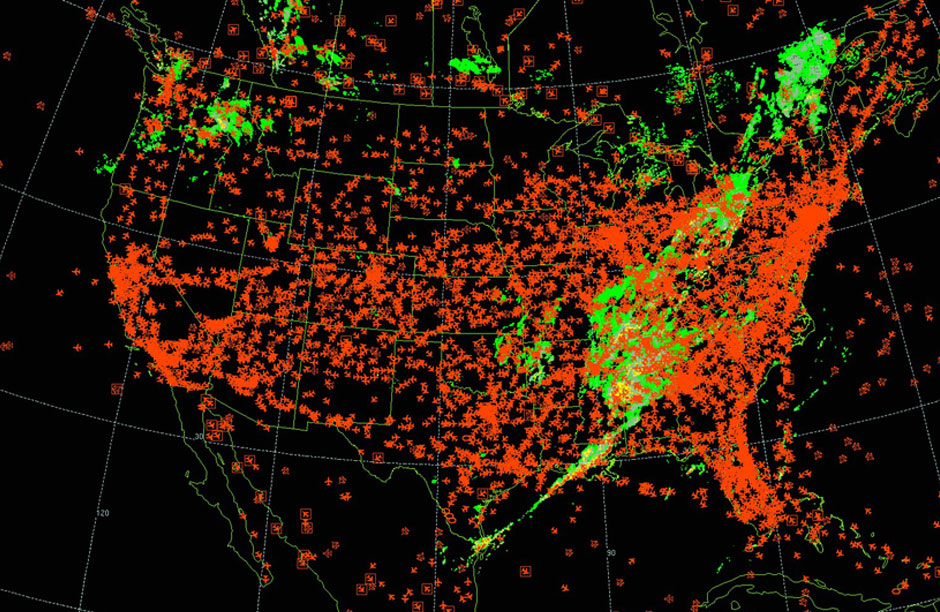

Noel Grundwaldt, "Untitled #20, 2008". Courtesy Stellan Holm Gallery Gallery A snapshot of the air traffic flow over the United States at 9:00 am EST

A snapshot of the air traffic flow over the United States at 9:00 am EST Noel Grunwaldt, "Untitled #19, 2008" Courtesy of the artist and Stellan Holm Gallery

Noel Grunwaldt, "Untitled #19, 2008" Courtesy of the artist and Stellan Holm Gallery Noel Grunwaldt, "Untitled (Hawk #3"), 2008, Courtesy Stellan Holm Gallery

Noel Grunwaldt, "Untitled (Hawk #3"), 2008, Courtesy Stellan Holm Gallery

Migration Interrupted

By Leila SamiiFor generations on end, birds have remained in the same migration patterns, returning to an unchanged safe haven they knew would be there.

This was the case for the Brown Pelican, recently removed from the federal endangered species list last fall. Normally taking a path to Mexico or Southern California, these birds have experienced an immense interruption in their migration patterns due to the oil spill. “ There are a billion birds that fly through here. The vast majority will be unaffected. But thousands will die,” explained Matthew Guttman, national correspondent for ABC News Radio.

One of the specific programs currently working in the Gulf Coast is Ducks Unlimited, the world’s leader in wetlands and waterfowl conservation. Dr. Tom Moorman of Ducks Unlimited, Director of Conservation Planning in the Southern Region spoke sheds light an issue that is still emerging. “Unfortunately, the species of migratory birds in question are “hard wired” to migrate to the coastal wetlands and beach habitats of the Gulf Coast. These programs cannot stop them, nor are they really intended to stop them so much as offer alternative habitat to birds that may find oil-damaged habitats upon their arrival in coastal areas. [Our] goal is to provide this habitat as alternative feeding areas for birds possibly displaced from oil-damaged marshes along the Gulf Coast.” While endless efforts such as Ducks Unlimited have continued to drive forward with full force, many researchers have come to terms with the fact that the invisible paths that are taken by these species are disappearing, and the small window we have to fully figuring them out is closing at a faster rate than ever before.

Nigel Brothers, a biologist well aware of this problem, recently recognized the disappearance of the Torresian imperial pigeon population ranging from Papua New Guinea to the Great Barrier Reef. Given that there is so much more to learn about migration as a whole, to see a species simply disappear during their migration with no explanation is disturbing to say the least. The disappearance of the birds is eerie on its own, but the deterioration of the paths and patterns they take is even worse.

Within our own species we ironically experienced a comporable halt with the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano. Migration was put on hold—airports were closed, flights were delayed, then cancelled, then rescheduled, then not. Phone lines jammed, trains overbooked. To imagine the obsolete dissipation of this path of travel would certainly put many in a state of despair. Meanwhile, more and more birds are facing a permanent state of what we experienced for only a short amount of time. The Red Knot bird, regularly summering in the Arctic and spending its winters in Tierra del Fuego, normally makes a critical stop in North America’s Delaware Bay. As a result of extensive commercial harvesting of horseshoe crabs, which produce the eggs that the Red Knot depends on for food, there has been a large drop in the birds’ population. Less crabs, less crab eggs to eat for the birds.

It is not an intangible thought to see how migration affects us, more specifically how the disintegration of these paths could cause more harm than expected. Take bees migration. If this small species’ migration were to be interrupted, certain plants would not be pollinated, essentially damaging our agricultural systems to a larger extent than we would think. “The phenomenon of migration is disappearing around the world,” expressed Dr. David Wilcove in his new book “No Way Home”.

To give proper attention to an issue that is invisible to the human eye, something that is constantly moving and not the easiest to track, may be one of the most difficult environmental undertakings we have had to face in awhile. Migration is being eradicated most directly by humans. Of course, many are not aware of this fact, and to think of an easy solution for the damage we have done is nearly impossible. Unlike most problems which are stable, can be contained, quarantined, and fixed; migration is an international phenomena that is literally always on the move. Fortunately, according to Moorman, programs concerning the oil spill, “were already established due to partnerships among state and federal agencies, and non-governmental organizations in the United States centered on wildlife conservation. The model was in place, requiring only funding to move quickly. Ducks Unlimited and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation had existing partnerships, and when BP agreed to donate proceeds from their share of the recovered oil in the Gulf, NFWF was able to quickly develop a grant program,”. Preemptive efforts such as these are displaying the necessary thought process we need to adopt in order to save these delicate migration paths. As we delve further into attempting to solve the mystery that is the deterioration of migration, we must keep in mind, as Dr. Moorman put it, how “North America has a rich history of wildlife conservation because the country ultimately was built on the foundation of its abundant natural resources. It is part of our history, part of our culture. It links us to our past and should be the foundation of our future.”