PAST ISSUES

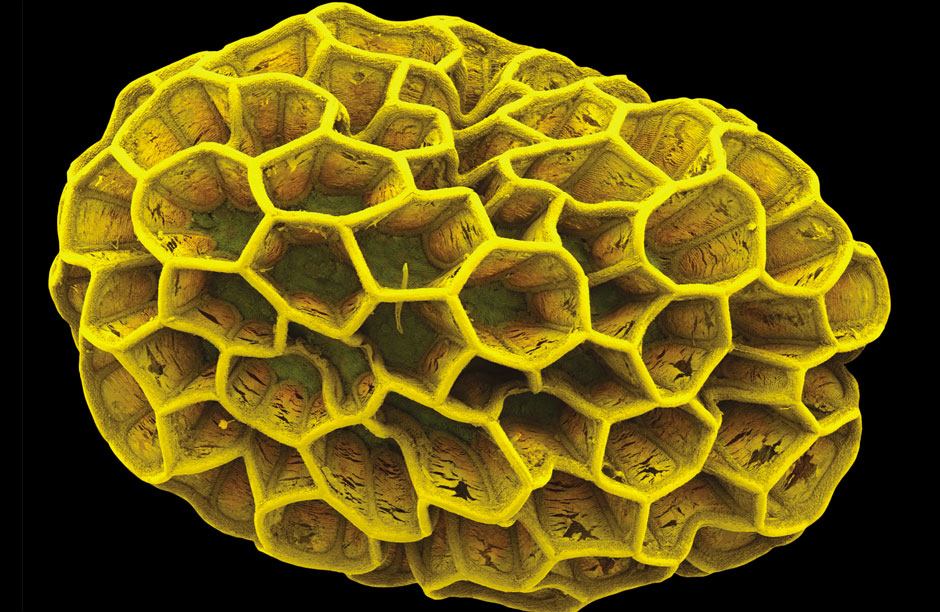

Silene gallica (Caryophyllaceae). Collected in Greece. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis Publisher

Silene gallica (Caryophyllaceae). Collected in Greece. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis Publisher Loasa chilensis (Loasaceae) collected in Chile. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis Publisher

Loasa chilensis (Loasaceae) collected in Chile. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis Publisher Trichodesma africanum (Borginaceae). collected in Saudi Arabia. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis

Trichodesma africanum (Borginaceae). collected in Saudi Arabia. Image from "Seeds:Time Capsules of Life" © Rob Kesseler, Wolfgang Stuppy & Papadakis

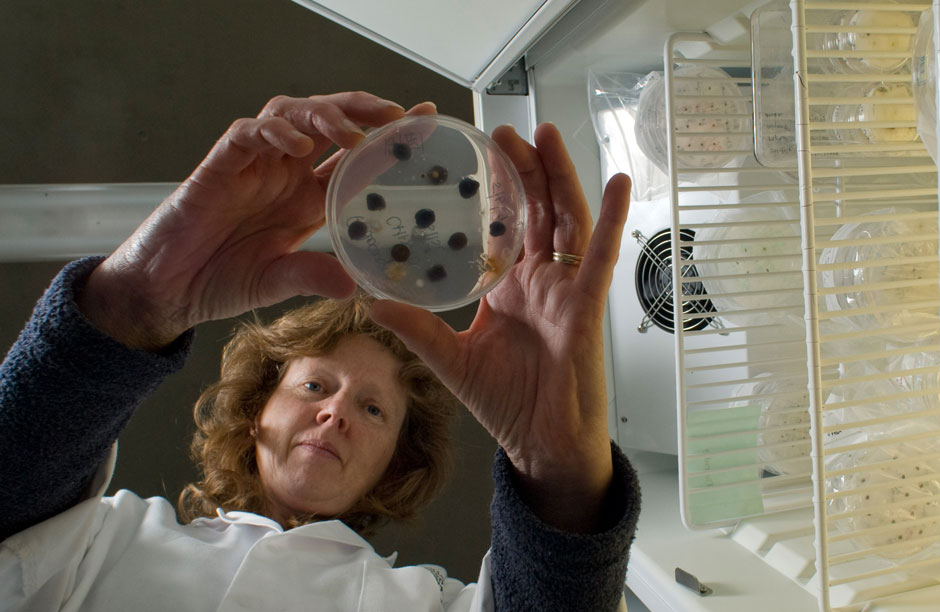

Samples being checked and stored at the Kew Millennium Seed Bank where the seeds of 10% of the world's wild species of plants is stored. By 2025 they expect to reach 25%.

Samples being checked and stored at the Kew Millennium Seed Bank where the seeds of 10% of the world's wild species of plants is stored. By 2025 they expect to reach 25%. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault on Spitsbergen Island in Norway protects samples of the seeds to all the major food crops on the planet.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault on Spitsbergen Island in Norway protects samples of the seeds to all the major food crops on the planet.

A Kew partner scientist retrieving samples of native flora in Africa.

A Kew partner scientist retrieving samples of native flora in Africa.

Noah’s Ark of the 21st Century

By Nicole DavisToday I reached for a grape. I popped it in my mouth and cracked through its center in one bite. The skin separated from the flesh, the juice pooled under my tongue and my back molar came crashing down on a small coarse pellet. Instantly, I winced and spit the dismembered pieces of the grape into a napkin. Resting among the saliva and soft pulp were four dark brown seeds. I didn’t expect them to be there. I couldn’t even remember the last time I had eaten a grape with seeds. To a seed scientist, seeds are architectural masterpieces, they are objects that can outperform any of our most treasured electronic gadgets and they are the messengers of some of the oldest wisdom this earth has to tell, but to many they are just four irritating pellets that have stood in the way of enjoying a juicy grape.

Who truly knows the value of a seed? Does anyone enter their supermarket and recognize all the produce and the food on the shelves (yes, think again, that also includes animal products) as the end product of one small seed? If we did, what a powerful lesson it would be to learn that something so small could make such a very very large impact.

In 1898 scientists at the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in Surrey, England started to gather a small collection of seeds. They began modestly with local wild flora. By 1973 an official seed bank was initiated and in 2000 the Kew Millennium Seed Project was launched in partnership with 123 institutions in 54 countries across all the major regions of the world.

The collection’s focus is on wild and native plant-life faced with the threat of extinction and plants with most use to the future. By 2010 they pledged to bank 10% of the world’s wild plant species. Today they have successfully reached that marker with a total of 1, 654, 753, 608 seeds representing 27, 651 species, 12 of which are globally extinct in the wild. Their goal for 2025 is to reach 25%. Apparently the value of a seed is a very serious matter to a small dedicated group of people.

Wolfgang Stuppy, one of the senior seed scientists of the Millennium Seed Project Team since 2003 emphatically describes their relevance:

“Plants are truly amazing. Unlike animals, they have the remarkable ability to use sunlight to make sugar from just water and carbon dioxide. In doing so, they not only produce their own food but also feed – either directly or indirectly – all animals and people on Earth. Furthermore, as a by-product, they produce the oxygen in our atmosphere. Quite simply, without plants we would not be able to breathe or eat… Plants play an important role in our lives in so many different ways, but because they seem static and make no sound, most of us do not think of them as true living beings.”

Personally, I have always been drawn to the symbolic power of seeds and how they can undergo the most profound transformation right before our eyes. I can take those very same grape seeds I spit into my napkin, add a small amount of water, place them under a cupboard and a few days later a sprout will emerge. Somehow 1 + 1 becomes three, an equation of pure alchemy – the equation of life.

In fables and folklore seeds have always embodied the notion of magic. Jack and his magic beans is not so far from the truth when, in fact, the largest living organism on the planet is a grove of Aspen trees covering a span of over 100 acres and the tallest is a towering Redwood reaching almost 400 feet towards the heavens.

On a microscopic level the story behind seeds doesn’t become less mysterious, instead their complexity is compounded when each seed’s unique and elaborate construction is revealed. With the aid of a microscope, photographer Rob Kesseler documented the extraordinary diversity and cleverly adapted design of seed structure. The vivid colors and intricate shapes of dozens of seed specimens are featured in the book “Seeds: Time Capsules of Life” written by Wolfgang Stuppy and Rob Kesseler with a forward by HRH Prince Charles of Wales as part of an initiative to raise awareness about the need for seed conservation.

Seeds, which appeared on this earth over 360 million years ago, have often adapted to specific animals in order to utilize them as the carriers and facilitators for their dispersal. “Another awe-inspiring aspect of seed and fruit biology,” Stuppy explains, “is the existence of fruits and seeds which are adapted to be dispersed by long-extinct animals. Such anachronistic fruits and seeds are found on all continents, for example the Osage orange (Maclura pomifera), a large, grapefruit-size fleshy fruit that simply drops off the tree and rots because the original dispersers used to be among the extinct ice-age megafauna that disappeared from America circa 13,500 years ago. I find the idea that the existence of such awesome and iconic beasts such as mammoths, ground sloths, and mastodons is still reflected in today’s plants who once shared the same habitat with them absolutely intriguing!”

The importance of collecting and preserving seeds is not just limited to Kew. There are hundreds of seed banks all across the world, both private and national, each specializing in various categories of plant life. Kew and its partners represent all those that specialize in native wild species, but when it comes to food crops it’s very rare to find a native species. In the United States, for example, some of the only native food crops are blueberries, cranberries, some nut varieties, tubers and some legumes and squash. Cultivated crops, like the well-known monocultures of wheat, soy, corn, and rice are vital to the world’s food security. Wheat alone provides more food for the human race than any other plant or animal. The seeds of cultivated food crops that have developed advantages over centuries through propagation, hybridization, and natural selection are the main focus of some of the world’s largest seed banks.

On the glacial island of Spitsbergen, Norway just 800 miles south of the North Pole there is an entrance to an underground vault tucked inconspicuously beneath the icy blankets of the Svalbard glacier. The cryptic chamber is, by nature, at a perfect temperature for storing seeds. Named the Svalbard Global Seed Vault after the glacier that conceals it, this seed bank was built with the aim to safeguard against loss of crop diversity globally.

After only 2 years in operation the Seed Vault already has over 400,000 seeds and has also already acquired a nickname: The Doomsday Vault. The remoteness and design of the facility appears at once ironically lifeless to be storing so much life and comically inaccessible for those recently afflicted by a nuclear fallout.

Kew’s facility is, on the contrary, an active facility bustling with scientists, lab technicians and visitors. The seeds of each plant species stored at Kew are tested every ten years for viability and replaced if necessary. “At one end of the spectrum there are species that will almost certainly survive in the seed bank for thousands of years but at the other end there are species that will probably only survive for a decade or two at best.”

Stuppy broke down the longevity of some popular seeds: sunflower seeds retain their viability for c. 165 years, lettuce for 447 years, soybean for 1,122 years, wheat for 5,079 years and sugar beet for 10,542 years. To play it safe Kew likes to keep at least 5,000 (and ideally 20,000) samples of each species’ seed in storage. In tandem the scientists at Kew are actively developing better methods for seed storage through the advancement of seed research. Both Kew and The Svalbard Global Seed Vault fulfill important roles in preserving plant diversity globally.

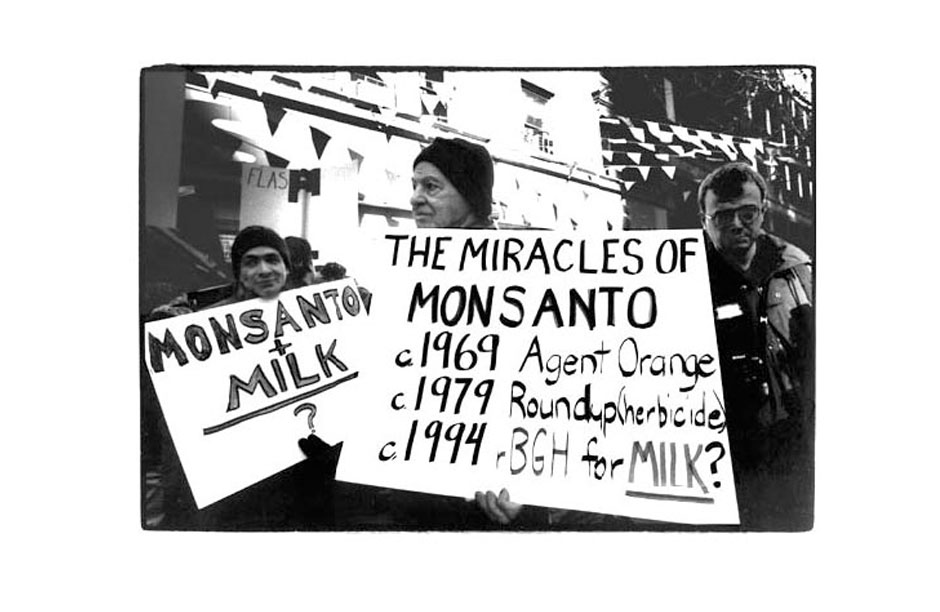

On the other end of the spectrum there is another group of people that know the value of seeds, in fact that value comes in the form of a 7 figure number: 4.5 billion American dollars – that’s last year’s profits for the St. Louis-based chemical and biological company Monsanto. They are the most popular villains of the agricultural world, and best known for their broad range herbicide “Round Up” – they were also the masterminds behind Agent Orange. (The company’s very first product was actually another notorious death agent, the chemical substitute for sugar: saccharin).

In 1945 Monsanto entered agribusiness with their weed killing products when government subsidized chemical research utilized during World War II could finally be put to commercial use.

Then in 1980 the United States Supreme Court ruled by a paper-thin margin that a genetically engineered bacterium capable of dissolving oil spills was patentable. Immediately thereafter Monsanto began buying up as many seed companies as they could accumulate and poised themselves to move into new terrain – the genetic modification of life.

After years of research and testing, Monsanto finally released their first genetically modified seed – a soy seed resistant to their Round Up herbicide, guaranteed to grow and survive. Genetically modified Canola, cotton and corn seeds followed the next year. All of them were quaintly dubbed “Round Up Ready”.

Monsanto’s seeds are all patented. Farmers must pay for their Monsanto seeds each sowing season, and at harvest they cannot save seeds from their crop as farmers have done since the beginning of farming. Instead, they must repurchase them for the next sowing season. As it turns out the eyes and ears of Monsanto are sharper than the CIA (some would even argue they are the same eyes) and the consequences of seed saving have proven very severe for a number of farmers.

The first genetically modified food on the market was a tomato. We see words like non-GMO slapped on our products, and hear the buzzword “heirloom” among organically minded circles, but aside from the dull taste of non-heirloom vegetables most of us do not know the true implications.

The problem is, most people really don’t know the implications of GMOs on human health. The research has been narrow and purposely quelled by impenetrable forces such as national governments and multi-billion dollar companies like Monsanto.

Jeffrey M. Smith published a book titled “Seeds of Deception” to outline all the potential risks of GMOs. His disclaimer is that the book is intentionally sensational as a tactic to grab the attention of the public, but the content is not falsified or exaggerated, the information is innately sensational.

For example, in 1999 Arpad Pusztai a Hungarian-born scientist discovered and made public that potatoes genetically engineered to produce their own herbicide caused health failure in rats – potatoes that were already being consumed by American and British citizens for over two years. Shortly thereafter he was fired from the Rowett Institute of Nutritional Health in Scotland where he had served as a head researcher for 30 years.

Smith separates the chapters in his book with anecdotal stories he collected concerning the natural refusal of animals when offered genetically modified crops. He tells of a flock of geese in Illinois that ate from the same soy field each year, but the year the owner of the farm decided to switch half his field to Round Up Ready Soy they ate only from the half of the remaining non-GMO crop. Then there is the cow farmer in Iowa who was amazed when his incessantly hungry cows wouldn’t even touch the GMO corn he put in their troughs. And, my personal favorite, a Dutch farmer plagued by mice in his barn decides to use them as constants in a homemade GMO preference test. He made two piles, one of non-GMO corn, and the other GMO and left the barn till morning. The next day the non-GMO pile was gone. The other remained untouched.

Unfortunately, rats and animals aren’t always the most convincing whistle blowers for humans, but in 2003 there was another study done in England on 19 human volunteers by the University of Newcastle. After feeding the volunteers soy dishes prepared from genetically modified soy products the researchers took stool samples which disproved one popular claim that any genetic material inserted digestive processes. It also left the researchers wondering if horizontal gene transfer had occurred, the implications of which could be very serious not just for humans and animals, but for plants too.

Jeffrey M. Smith pinpoints other concerns aside from “horizontal gene transfer” such as “antibiotic resistance”, “allergens”, “genetic code scrambling”, “genetic stacking”, “waking sleeping viruses”…and the list gets more sci-fi as the pages turn. The only trusty, recognizable threat he names is cancer. This is the main problem. With the rise of any new frontier from the internet to genetic engineering – a host of unknowns will likely result in some unwanted and dangerous results. And it doesn’t help that the laws of these new frontiers echo the lawlessness of the wild west.

When I asked Wolfgang Stuppy about Kew’s perspective on GMOs he replied, “The Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew has a neutral position to GMOs and does not carry out any research in this field.” Instead, he emphasizes, “We believe that wild species are an untapped resource for crop improvement through ‘traditional’ plant breeding in agriculture, horticulture and forestry. We believe we should start here first.” When he said this, I remembered a story I read from the book The Compassionate Universe by Eknath Easwaran about Jivaka a famous Indian physician who is said to have served as the Buddha’s personal physician:

“Before graduating from the ancient Indian equivalent of Harvard Medical School, Jivaka and his classmates were given a final examination. Each was handed a basket and sent into the forest to bring back any herbs or plants that had no medicinal use. All the other interns brought back armfuls of flowers and leaves, but Jivaka returned empty handed. When he came before his surprised teacher he explained: “We may not know it yet, but there is use for every tree, herb, plant, and flower in the forest.”